Motherhood & Marie Antoinette

examining the notorious French queen through the lens of motherhood, the role that was meant to define her life

“I am marrying a womb.”

Napoleon Bonaparte on his marriage to Marie Louise of Austria, the great-niece of Marie Antoinette, 1810

“My title of mother assures my links [with France] forever.”

Marie Antoinette, 1790

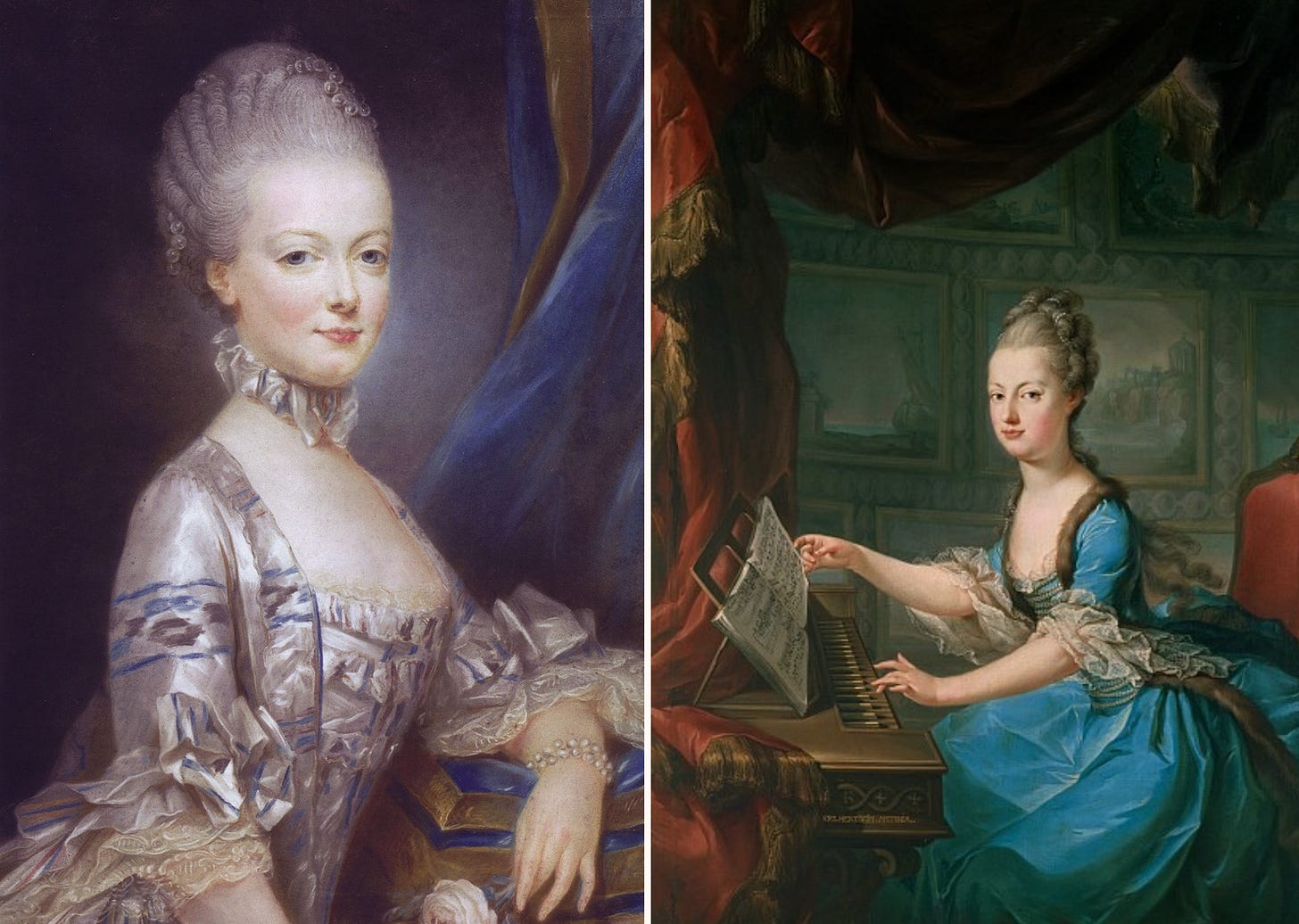

“Little Madame Antoine”, the youngest daughter of the stalwart Austrian Empress Maria Theresa, would not ordinarily have been chosen to bear the future king of France. Her own mother described her as neither the brightest nor the most beautiful child. Her tutors complained of her ineptitude in reading, writing, and speaking. She had a reputation for being too curious, too frivolous, too friendly with servants and commoners.

But by 1767, an alliance with the French kingdom was imperative—a marriage had to be made. Having lost her more eligible daughters to marriage or illness, Maria Theresa’s only remaining option was Antoine. So, barely twelve, the young Archduchess was betrothed to the Dauphin of France1, Louis-Auguste. From that point, the unity of two major European powers depended on one flighty preteen’s ability to bear a child.

From the start, it was made clear that Antoine’s charm and warmth would have to make up for her supposed inadequacies. Throughout her adolescence, her mother reiterated that these gifts would be her only saving grace, adding:

It isn’t your beauty, which is frankly not very great, nor your talents nor your brilliance (you know perfectly well that you have neither).

When visiting French officials further deemed the twelve-year-old’s appearance “unsatisfactory” for a royal wedding2, Antoine underwent a transformation befitting Mia Thermopolis, albeit at a far more impressionable age and with far less Disney magic.

For three months her crooked teeth were fixed to a horseshoe-shaped piece of metal known as Fauchard’s Bandeau, a painful precursor to braces that could easily be mistaken for a medieval torture device. French hairdressers accommodated her “uneven hairline” by teasing and shaping her strawberry blonde tresses. Corsets and pads were used to compensate for a “flat bust and uneven shoulders”. Torn down and rebuilt from the ground up, Antoine completed her bridal metamorphosis by adopting a new identity. For the rest of her life, she would be known as Marie Antoinette.

At fourteen and fifteen, respectively, Marie Antoinette and Louis-Auguste were wed in a larger-than-life Versailles ceremony, a veritable extravaganza with 6,000 in ticketed attendance alone3. A massive firework display was set to follow the reception, but it was cancelled due to inclement weather. Ironically, no metaphor could be more appropriate for the wedding night that would follow.

Marie Antoinette knew what to expect on the night of her wedding. Her mother, who meticulously tracked the menstrual cycles and marital relations of her daughters, would certainly have shared the details necessary for procreation. When the new Dauphine woke to an empty bed, no more “wifely” than she had been upon her arrival, she was likely confused and disappointed. Questions that already plague most teenage girls were intensely magnified: Had she failed her only assignment? Was something wrong with her?

She would come to learn that her new husband possessed a disastrous combination of extraordinary shyness and complete cluelessness. For seven years, Louis-Auguste rarely visited his wife’s bedchamber. When he did, solely out of obligation, he never fully consummated their marriage. The truth was, he didn’t understand just how to produce an heir. He lacked any real sex education, having been neglected for most of his life4 and orphaned by age eleven. Medical records also indicate that the Dauphin suffered from a condition which may have made intercourse quite painful. So, Louis-Auguste kept to himself. During the days, he focused on his hobbies of hunting and locksmithing. In the evenings, he chose to sleep alone.

For her part, Marie Antoinette became the subject of nationwide condemnation. Rumors circulated about an annulment and her imminent replacement. She was labeled a cold and taciturn Austrian, unable to inspire passion in her husband—though if she dared to smile, she was vilified for being irreverent, incapable of taking her position seriously. As years passed, it became increasingly difficult for the Dauphine to gain a foothold in her new kingdom, while her husband’s contribution to the problem of an heir garnered far less attention.

To remedy the situation, Marie Antoinette tried to insert herself into the Dauphin’s world. She joined him on his hunts and acted as his confidante. The two developed a close friendship, even claiming to be in love, but their marriage remained childless. In 1775, Louis-Auguste was crowned King Louis XVI, still with no heir to speak of.

After seven years of uncertainty, a frank discussion with his brother-in-law seems to be all it took; following a Hail-Mary effort from Marie Antoinette’s elder brother, Louis-Auguste finally fulfilled his marital obligation. At last, the Queen became pregnant. Having given up hope that she would ever become a mother, she spent the next nine months living in a dream.

A queen at Versailles could expect to give birth before an assortment of royal family members, but Marie Antoinette experienced the agonizing final stages of labor before a literal horde of onlookers. When her labor was announced, hundreds of curious spectators poured into her apartments. In later years, witnesses would recall how two chimney sweeps had climbed the furniture to get a better view.

Eight excruciating hours later, a baby girl was born, much to the disappointment of the audience who had hoped for a male heir. Immediately afterward, the Queen lost consciousness due to sheer exhaustion and a lack of oxygen among the crowd. She was also likely suffering from an internal hemorrhage, which would never fully be remedied. Sadly, her birthing attendant had been chosen for his connections rather than his skill.

“Poor little girl. You are not what was desired, but you are no less dear to me […]. A son would have been the property of the state. You shall be mine. . .”

Marie Antoinette’s first words to her daughter, 1778

The birth of a daughter necessitated an immediate second pregnancy for Marie Antoinette, but mercifully, the conception of this child would be far less tumultuous than her first. Following the birth of their daughter, Louis-Auguste became completely devoted to his wife. For many years, the pair enjoyed a loving, mutually respectful marriage. In a life bookended by uncertainty, inadequacy, and tragedy, these moments with her growing family would be some of Marie Antoinette’s happiest.

Just before her twenty-sixth birthday, she fulfilled her life’s mission by bearing an heir to the French throne. As Louis-Auguste tearfully gazed upon his newborn son, he turned to his wife and said:

“Madame, you have fulfilled our wishes and those of France, you are the mother of a Dauphin.”

Two more children would follow, but these pregnancies were much harder on the Queen. By her thirties, numerous miscarriages and complications sustained from childbirth had taken their toll. Fortunately, her deliveries were made easier with more private birthing quarters. In a break from centuries of tradition, only an intimate handful of spectators were permitted to enter.

Much of Marie Antoinette’s approach to motherhood went against the long-standing customs of Versailles. Inspired by Enlightenment ideals, she preferred to be heavily involved in her children’s lives, despite the general attitude that it was not a queen’s place to rear the “Children of France”. She insisted upon breastfeeding and oversaw her children’s education personally. She even adopted several children, including a young enslaved boy, Jean Amilcar, whose arrival at Versailles as a “gift” horrified her.

The Queen’s controversial maternal convictions led her to spend much of her time away from the formal court of Versailles. She retreated to the The Petit Trianon, a château on the palace grounds where she could provide her children a more simplistic upbringing. On site, she had a model village constructed, complete with an assortment of farm animals, a plethora of fresh florals, and hired “villagers”, who tended to the grounds and cared for the animals in the interest of pastoral authenticity. . .

Cosplaying provinciality in the midst of tragic, widespread poverty was tone-deaf at best, but this hardly mattered. By the time of the model village’s completion in 1786, the French Revolution was well underway and Marie Antoinette was already disastrously unpopular. She was a villain the angry masses could rally around, even if her contributions to the French financial deficit were minimal compared to her husband’s and those of his predecessors. She was foreign and she was a woman; it was easy to blame her for the suffering that had been slowly accumulating for centuries.

Her reputation as a liberated, progressive mother became the very ammunition used against her. Allegations of bastardy were regularly made against her children. Lewd pamphlets, published daily and widely circulated, detailed vulgar fabrications: the Queen enjoying nights of heavy drinking and debauchery, engaged in graphic sexual encounters. She was even rumored to be responsible for the death of her son. A far cry from her glory days as the mother of a Dauphin, she had become a monster.

“There were threats to shoot the Queen at Épernay—if she could be got without hitting the King.”

Antonia Fraser, on the final years of Marie Antoinette

A family portrait commissioned to highlight her maternal role only incited more condemnation. Noticeably heavier following the birth of her fourth child, with her hair shorn due to postpartum hair loss, the Queen was mocked for her appearance. For fear of an uprising, the portrait had to be removed from public view.

Eventually, the portrait was removed from Versailles as well. Sophie, the Queen’s youngest daughter, died not long after the painting’s completion. Her elder brother, the Dauphin, died two years later. Tradition forbade Marie Antoinette from attending the funeral rites, so the bereaved mother suffered alone. The family portrait became too painful a reminder for her to bear.

Forty days after her son’s death, French revolutionaries stormed the Bastille. Fearing persecution, a great majority of royals and nobles fled to the safety of neighboring countries. Louis XVI, however, was reluctant to leave France behind. Vowing to keep their family together, the Queen stayed by his side with their two remaining children, a choice that would ultimately prove fatal. After four years in various stages of imprisonment, Marie Antoinette was led to the guillotine at only 37 years old.

Almost 250 years later, Marie Antoinette remains a rather misunderstood figure. Even if we can look past her violent demise, her legacy is one of careless decadence, magnified by centuries of propaganda. We imagine her bejeweled fingers tossing a pair of dice while the French populace starves beyond her palace walls. Let them eat cake!5

I don’t mean to canonize her (particularly not from an eerily similar climate of wealth inequality and impetuous, out-of-touch leadership) but I do wonder whether the iconic French queen deserves a bit more empathy.

Joseph Caraud’s 19th century portraits of Marie Antoinette depict a loving, devoted mother. I find it poignant that these scenes were only imagined after her death when, during her life, they defined her. Though the accident of her parentage earned her the reputation of a deposed queen and an insensitive spendthrift, I think she would have preferred to be remembered as a mother first. After all, this was the role she was born to play.

As always, thanks for reading extracurriculars! For more deep dives & niche history like this, consider subscribing below.

For more on Marie Antoinette, check out these resources:

Marie Antoinette: The Journey by Antonia Fraser, a sweeping, intricately detailed biography of the French queen. Every time I open this book, I’m unable to put it down. The minute details Fraser includes truly bring Marie Antoinette to life.

Marie Antoinette, the 2006 film by Sofia Coppola based on Fraser’s book. This movie is visually stunning and, apart from some fun creative liberties, very historically accurate. I wore this DVD out in 2008.

The stunning artwork of Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, available via WikiArt. Most of Marie Antoinette’s most famous portraits were painted by Vigée Le Brun, the premier portrait artist for France’s most wealthy during the final years of the monarchy.

No Joke, Pratiksha Thangam Menon’s article for JSTOR, examines the insidious ways that humor can normalize hatred, bigotry, and eventually, murder. The piece opens with a discussion of the smear campaign against Marie Antoinette, alongside a pornographic cartoon typical of those created in an effort to dehumanize her. (NSFW warning, there’s a giant cartoon penis at the top of the article!)

the male heir to the French throne was known as the “Dauphin” (pronounced doh-fan); his wife was known as the “Dauphine” (pronounced doh-feen)

can we be so for real? let ye without an awkward preteen phase cast the first stone!!

this does not account for the audience that amassed on the grounds of Versailles; the scene was so chaotic that over 100 people were crushed to death by the crowds

like his wife, Louis-Auguste was not the first choice for the throne; he existed in his parents’ periphery until his smarter, more handsome elder brother died in 1761

though famously attributed to Marie Antoinette, this phrase was widely used a century before her time to reference the negligence of the noble class