The Year Without Summer

how recorded history's most destructive volcanic event changed the world forever

TW: this post contains descriptions of natural disasters, disease, & death; reader discretion is advised

Sumbawa, British East Indies1 - April 10, 1815

Beneath a palm thatched roof, wrapped in a richly patterned sarong, an anonymous woman prepares dinner for the evening. Her brow furrowed, she pads across the bamboo floor with intention. Where did she leave the good knife? Beside the hearth, a leg of goat waits patiently.

Her husband stands on the porch, overlooking the lush, verdant facade of Mount Tambora. In the twilight, the volcanic mountain takes on a blueish hue.

They are two of 10,000 residents in the kingdom of Tambora, a thriving agricultural community at the base of Mount Tambora’s twin peaks. For them, tonight is like any other night: a pot of rice simmers over an open flame, a series of copper bowls wait to be filled. Behind a large porcelain jar, the woman’s knife blade reflects the glow of the fire. She retrieves it and crosses the room once more.

Suddenly, a deafening explosion reverberates in the distance, rattling the home’s stilted foundation. From the peak of Mount Tambora, two flaming columns of volcanic debris burst into the stratosphere. A colossal, black cloud smothers the evening sky. Sheets of ash, hot rain, and pumice stones plummet to the ground at a wild pace, hurtled through the air by hurricane-force winds. The couple, along with their entire village, are consumed by a flaming vortex in seconds.

This eruption of Mount Tambora is considered the largest volcanic event in recorded history, its severity likened to an atomic bomb. It rained down ten times more debris than Mount Vesuvius had in Pompeii and Herculaneum two millennia before. Its magnitude was twice as powerful as the famed Krakatau eruption of 1883. In a single day, it erased an entire civilization, burying it beneath three meters of volcanic rock.

The ghosts of Tambora’s devastating impact still linger on the island of Sumbawa, where the population has never fully recovered, but the disaster’s effects were not confined to the East Indies. For three years following the blast, the volcano’s massive sulfate dust cloud remained trapped in the stratosphere, disrupting the Earth’s weather systems on a massive scale.

Global temperatures dropped drastically. Harsh droughts gave way to periods of relentless rain, flooding the land. Wildfires raged. Red snow fell in Italy while frost blackened the trees in the United States. Thick clouds of ash and sulfur dioxide hung in the sky, producing a yellow haze that gleamed red at sunset. The 1810’s would be the coldest decade on record; the year 1816 would be the coldest since the Middle Ages, forever remembered as “the year without summer”.

China began to feel the fallout from Tambora’s eruption as early as 1815, when incessant rains and thick, icy fogs destroyed both summer and fall harvests. For three years, unprecedented cold and wet conditions decimated crops, leading to a famine of unspeakable severity. In the southeastern Yunnan province, 32 year old Li Yuyang used poetry to cope with the horrors he and his family experienced. In 1816, he wrote:

"Rain falls unending, like tears of blood from the sentimental man. Houses sink and shudder like fish in the rippling water I see my older boy pulling at his mother’s skirt. The little one cries unheard. Money gone, and Rice rare as pearls, we offer our blankets to save ourselves."

Famine was not limited to China in the year without summer. Bitter cold, interminable droughts, and extreme flooding caused crops to fail across the globe. By 1816, potato fields in Ireland lay submerged beneath waist-high pools of flood water. Crop yields in England and Western Europe plummeted by 75% while snowdrifts piled five feet high. In the northeastern United States, farmers wore overcoats and mittens throughout the summer, harvesting what little they could.

As life hung in the balance, millions chose to abandon all they knew in search of (literally) greener pastures. In the US, migrants from the northeast loaded up their wagons and headed west for Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. Starving refugees from Italy, Germany, and Ireland fruitlessly searched for relief across the continent. Amidst these transient populations, airborne illnesses like typhus wreaked havoc.

But nowhere was disease more severe or more consequential than in India. By the end of 1816, prolonged drought and massive flooding created the perfect environment for cholera to thrive. India was no stranger to the disease; cholera had been appearing seasonally in the Bengal region for milennia. However, in the stagnant pools left over from torrential storms, a particularly virulent strain emerged. In early 1817, a traveling English clergyman described the scene:

The dead and dying are all huddled together in a confused mass, and several fires are blazing at the same time, consuming the bodies of the more rich and noble, who have just died, whilst the poor creatures who are expiring feel certain that in a few minutes their bodies must share the same fate […] the stench proceeding from the burning bodies, and the lurid gleams of the blazing fires reflected by the water […] furnish a scene of woe which completely baffles the power of description to portray.

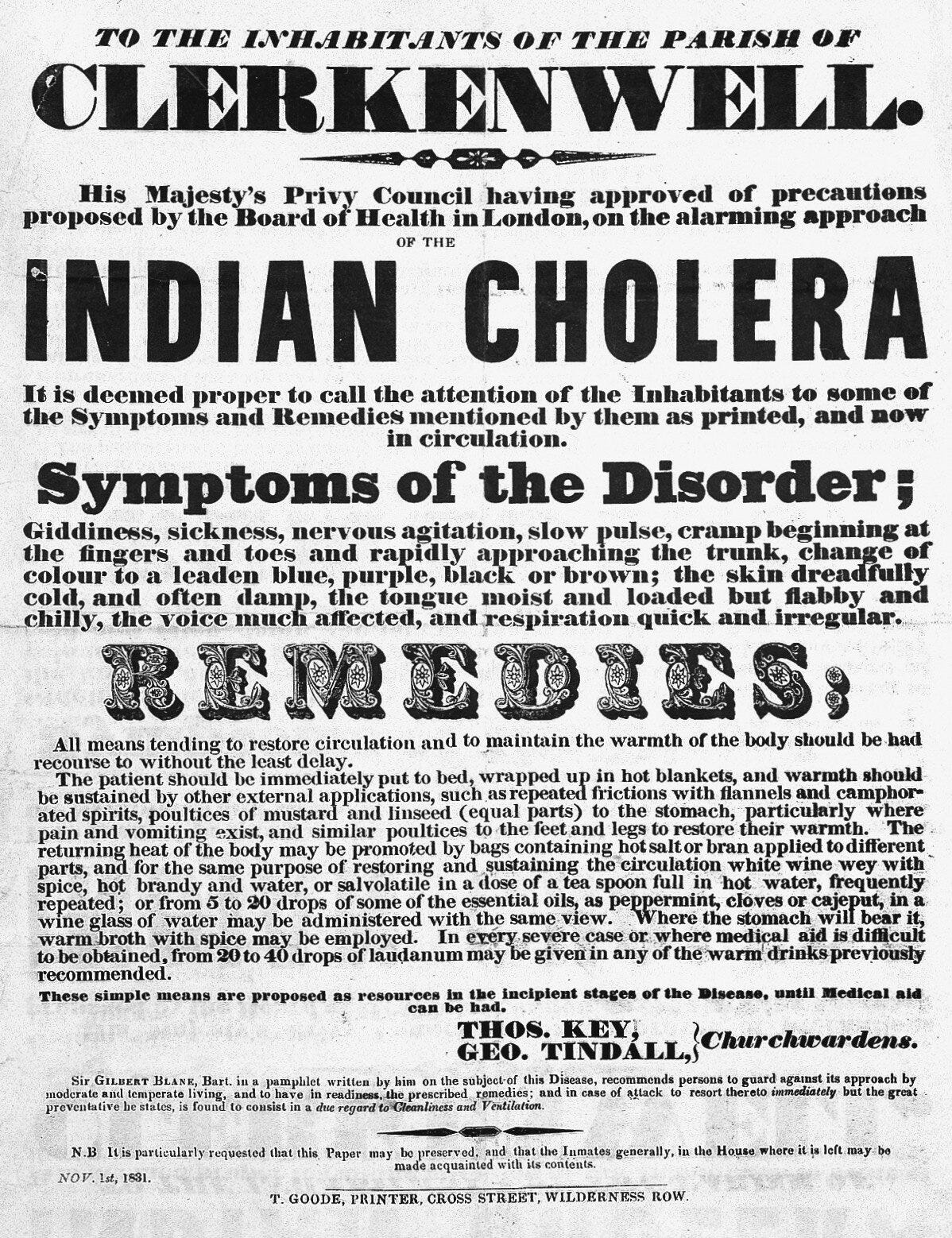

Carried along trade routes, the disease soon reached pandemic proportions. Cholera devastated the Asian continent through the 1820’s and reached Europe and the Americas by the early 1830’s. All told, by the time cholera crossed the Atlantic in 1832, Indian fatalities alone tallied in the millions.

During that tragic year of 1816, those not immediately concerned with the business of death and survival found themselves inspired by the apocalyptic weather conditions gripping the world. Paintings from the time depict skies of vibrant red and golden yellow, consistent with what we know about the appearance of atmospheric ash. Today, landscape paintings from the Tambora years (1816-1819) serve as our best understanding of what the world looked like during that harrowing time.

On the shores of Lake Geneva in 1816, a renown circle of English writers bemoaned the loss of their vacation to constant, intense storm activity. Shuttered inside their summer home, Percy and Mary Shelley, Lord Byron, and other friends gathered by the light of candles in the absence of the midday sun.

To pass the time, the group read from a collection of German horror stories until it was suggested that they each pen their own in a sort of horror story contest. Inspired by blinding flashes of lightning over the lake, Mary Shelley developed the story that would later become Frankenstein.

The Shelley’s literary circle would publish a breadth of work in the years of Tambora’s fallout. During that summer, on the balcony of his Lake Geneva home, Lord Byron penned “Darkness”, a poem detailing apocalyptic horrors witnessed at the end of the world. Much of “Darkness” reflects the world that Byron saw beyond his balcony in 1816: the disaster, the famine, the calamity, and of course, the darkness. The poem begins:

"I had a dream, which was not all a dream. The bright sun was extinguish'd, and the stars Did wander darkling in the eternal space, Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air; Morn came and went—and came, and brought no day, And men forgot their passions in the dread Of this their desolation; and all hearts Were chill'd into a selfish prayer for light: . . ."

Though Tambora’s sulfuric clouds would dissipate around 1819, the horrors of their three year stratospheric presence would completely change the course of history, bringing about about great leaps in the fields of agriculture, meteorology, and public health.

In 1820, the very first weather charts would be created in response to the lack of widespread weather reporting during the Tambora years. By 1835, when the electric telegraph was invented, weather reporting became more regular and more widely disseminated. Ten years later, German chemist Justus von Liebig would develop mineral fertilizers in order to prevent a famine like the one he had lived through as a child.

The recurring cholera pandemics of the 19th century left many medical experts scrambling to understand the disease’s causes. Public health boards were established around the world to mitigate the spread and severity of infection. In 1885, Spanish physicians developed the first cholera vaccine. Though cholera still remains a major threat in some parts of the world, these medical innovations have saved countless lives.

But all these great leaps in human art and innovation undoubtedly came at a great cost. The eruption of Mount Tambora incited tragedy on a global scale, changing the course of history forever. Hundreds of thousands lost their lives, and nearly everyone on the planet was impacted. Today, as we watch the effects of planetary warming unfold around us, it is hard not to imagine that the events of 1816 await us in a not so distant future.

We drift closer to a world without summer every day. Temperature fluctuations of only 5-6° resulted in widespread devastation between 1816-1819. Since then, the global temperature has increased by about 0.11° per decade. Tambora’s effects lasted three years; the compounded effects of planetary warming could last an eternity.

But one very important distinction separates 1816 from 2025: for the first time in the history of our species, we hold “the principal levers of control over biophysical conditions on planet Earth”2. Even when outlook seems dismal, we have to remember that the controls are in our hands. It is our duty to tilt them in the right direction, lest we repeat the horrors of “the year without summer”.

As always, thanks for reading extracurriculars! For more deep dives, obscura, & niche history like this, consider subscribing below.

For more, check out these resources:

The Year Without Summer by William K. Klingaman and Nicholas P. Klingaman & Tambora: The Eruption That Changed the World by Gillen D’Arcy Wood, both of which greatly informed this post.

“Darkness”, Lord Byron’s apocalyptic poem written from his Lake Geneva balcony in the summer of 1816.

The collected poems of Li Yuyang, written during the Chinese famine between 1815-1818. Trigger warning for descriptions of children’s suffering

Schubert’s Symphony No. 5, completed at the end of 1816, explores themes of struggle and triumph. Was Schubert manifesting better conditions following a year of widespread strife? Noticeably absent are trumpets and drums; had he perhaps heard enough thunder? You be the judge.

Up From The Ashes, Emma Johnston’s article for Popular Archaeology which details the 2004 findings in the lost kingdom of Tambora. The web page is rough, but the article is well worth it!

Anti-Asian Racism in the 1817 Cholera Pandemic, Sagaree Jain’s article for JSTOR examining the racial hostility borne out of India’s 1817 cholera outbreak—fittingly published in April of 2020.

My post about the Oneida Community, a religious cult influenced by the westward migration of the early 1800s. As migrants flooded into western US territories during “the year without Summer”, new settlements often became hotbeds of religious revival, as people escaped what they could only assume was a punishment from God. On one hand, religious revival contributed heavily to social reform and the abolitionist movement. On the other, it created some dangerous religious cults. Check out my post to learn more about the latter!

modern day Indonesia

Wood, G. D. (2015). Tambora: The eruption that changed the world. Princeton University Press.

Fascinating article, I did not know about this and now want to find out more. Thanks

If you think we hold the levers to control weather through our carbon emissions then I urge you with all speed, move to China and lobby their dictatorship to stop building coal power plants. They are the largest emitter by far, and if they don't change, and you're correct, then there truly is no hope.

But then again, you could be wrong. Record ice levels in Antarctica, and all of Al Gore's doom predictions being wrong, are tending in that direction.