The Beach Pneumatic Transit

Alfred Ely Beach & the underground transit system lost beneath NYC’s streets

For today’s post, you’ll be heading back to New York City in the year 1870. For your sake, we’ll choose a nice, clear morning in May— though “clear” is a bit relative. You’ll notice an ever-present industrial smog hanging along the rooflines.

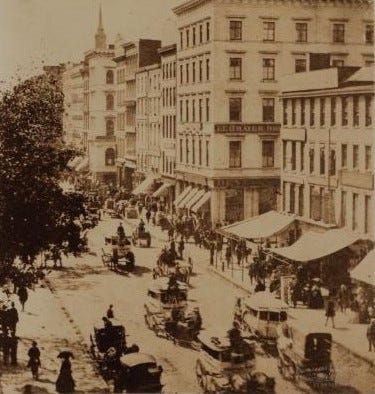

Your visit begins with a walk along Broadway’s bluestone sidewalks. By today’s standards, you’d be in downtown Manhattan, but in 1870, this is the heart of the city. Above your head, the colorful awnings of street-level storefronts ripple in the breeze. Bells, whistles, and shouts ring out from every direction. Hooves and creaking carriage wheels rhythmically pound against the cobblestones beside you, the sounds of the city’s main source of transport echoing through a canyon of five-story buildings.

New York City is rapidly entering the modern era, and this is evident in the constant hum of factory production and the lingering sulfuric smell of gas-powered streetlights. The burgeoning metropolis is more crowded and chaotic than ever before; one million people walk alongside you through Manhattan’s 19-square miles of urbanized area, and much like today, everyone has somewhere to be.

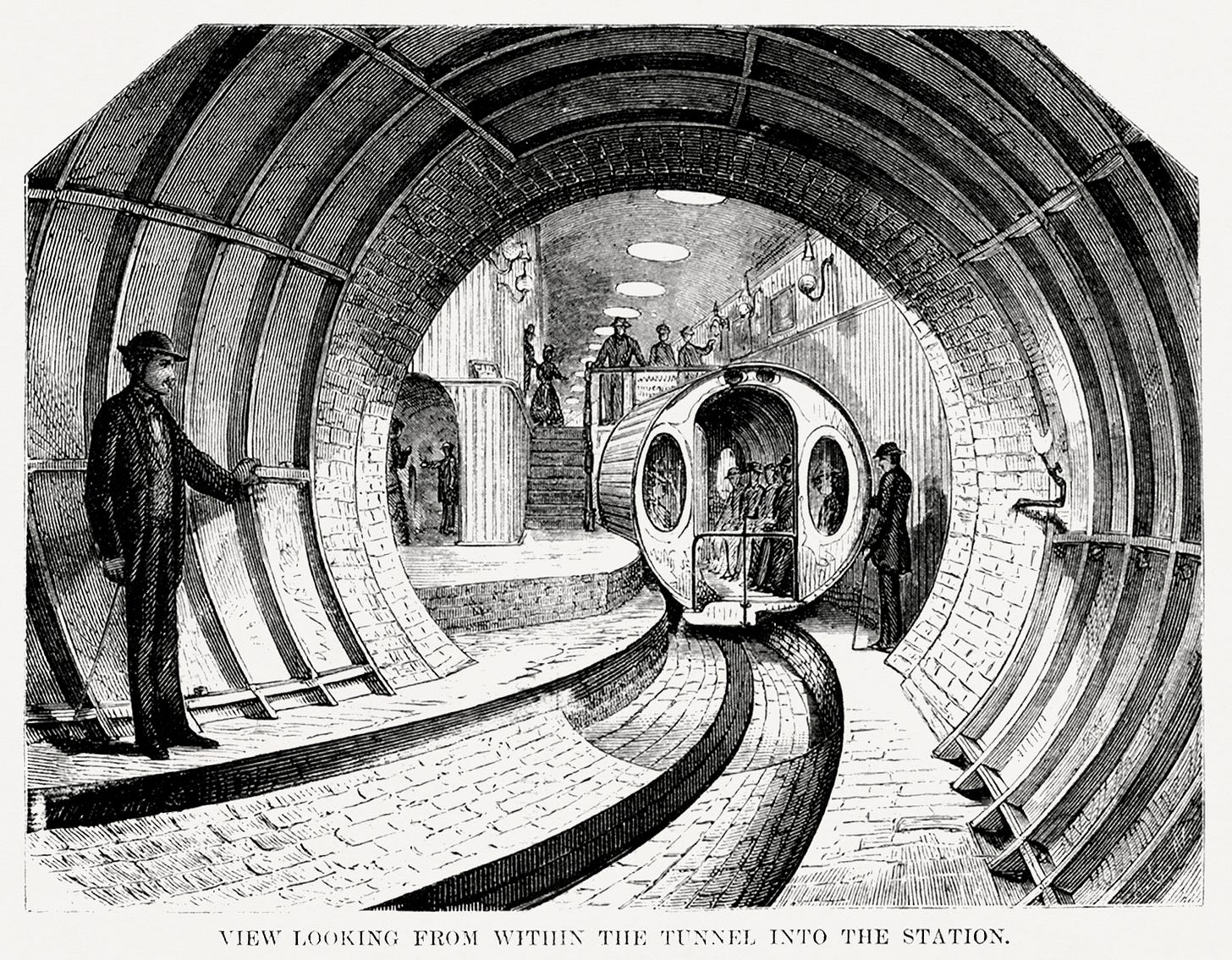

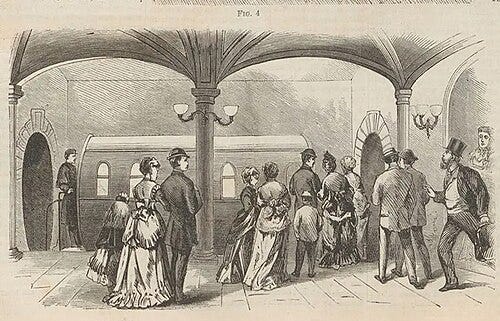

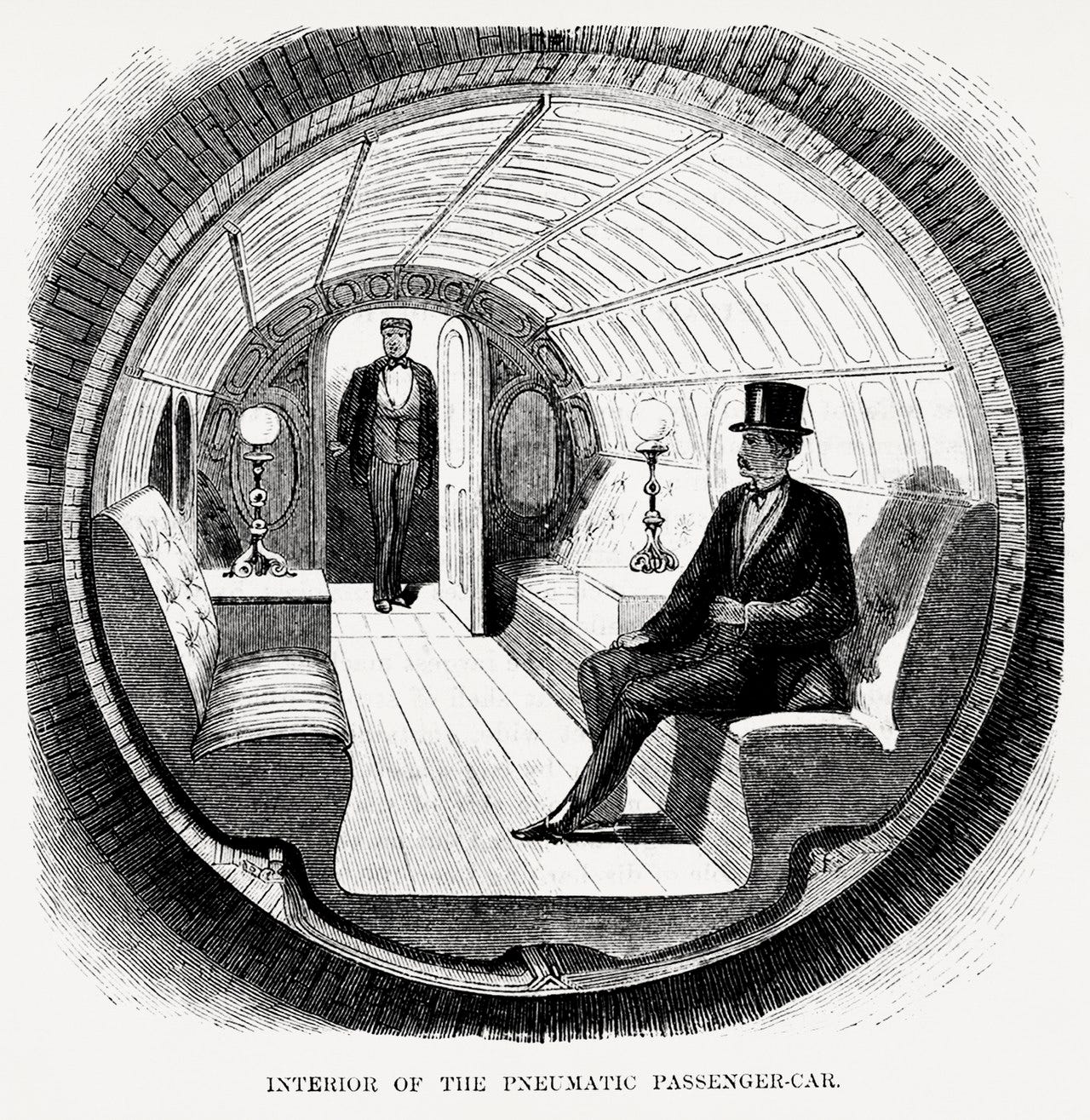

In an escape from the sensory frenzy of the city streets, you descend a flight of stairs at the corner of Warren Street. Slowly, the outside world fades away—you can hardly smell the leather tanneries and slaughterhouses from here! You enter a cavernous, underground terminal with the air of a hotel lobby. Gilded frames and mirrors ornament the walls. The ceiling is adorned with pastel-toned romantic frescoes. Mellow piano music fills the air while zirconia lamps bathe the scene in warm, incandescent light.

From an ornate brick tunnel, flanked by bronze statuettes, a passenger car quietly pulls in and comes to a stop. Notably absent are the sparks and smoke of typical rail travel; a modern form of transport for the modern age, this passenger car harnesses the power of air.

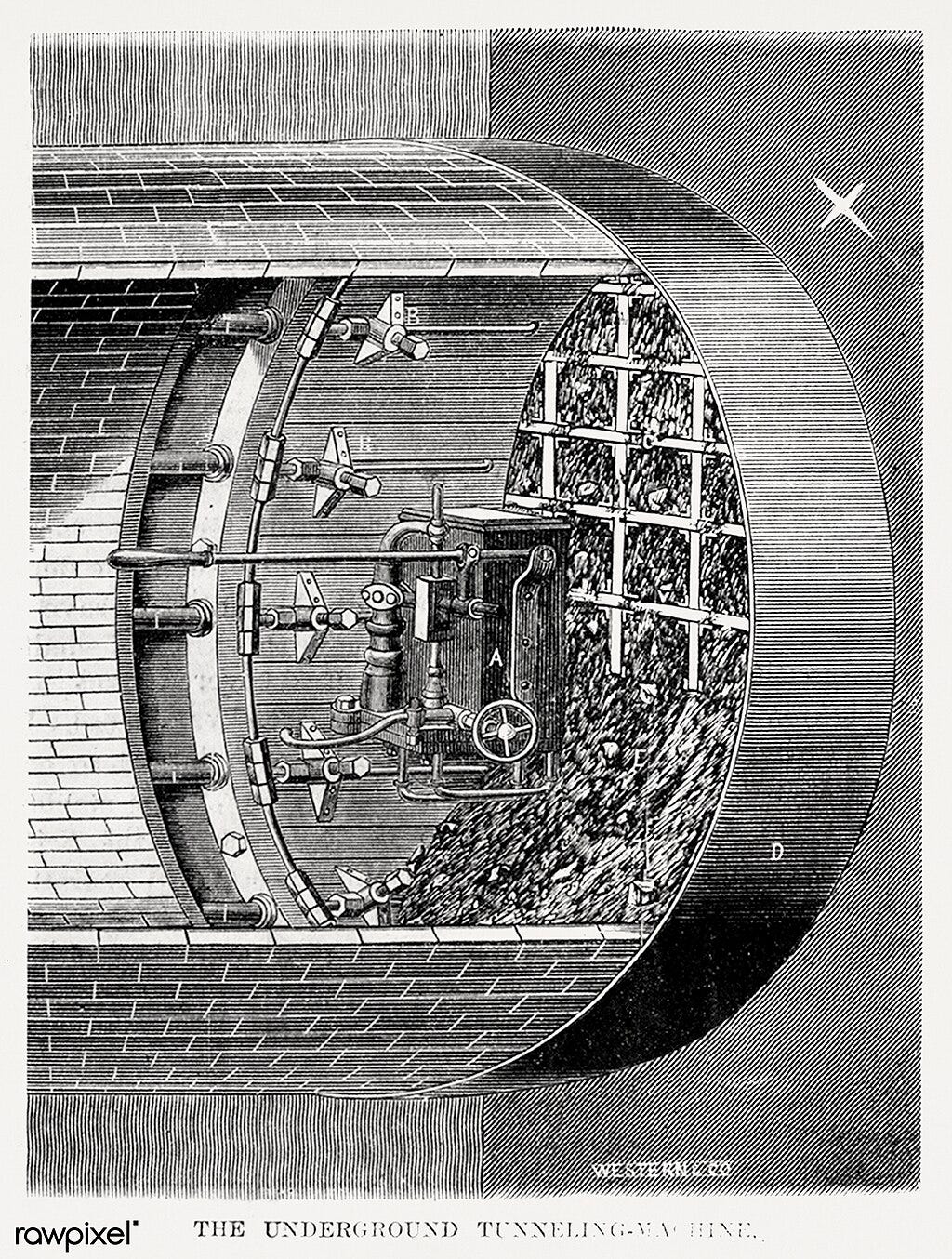

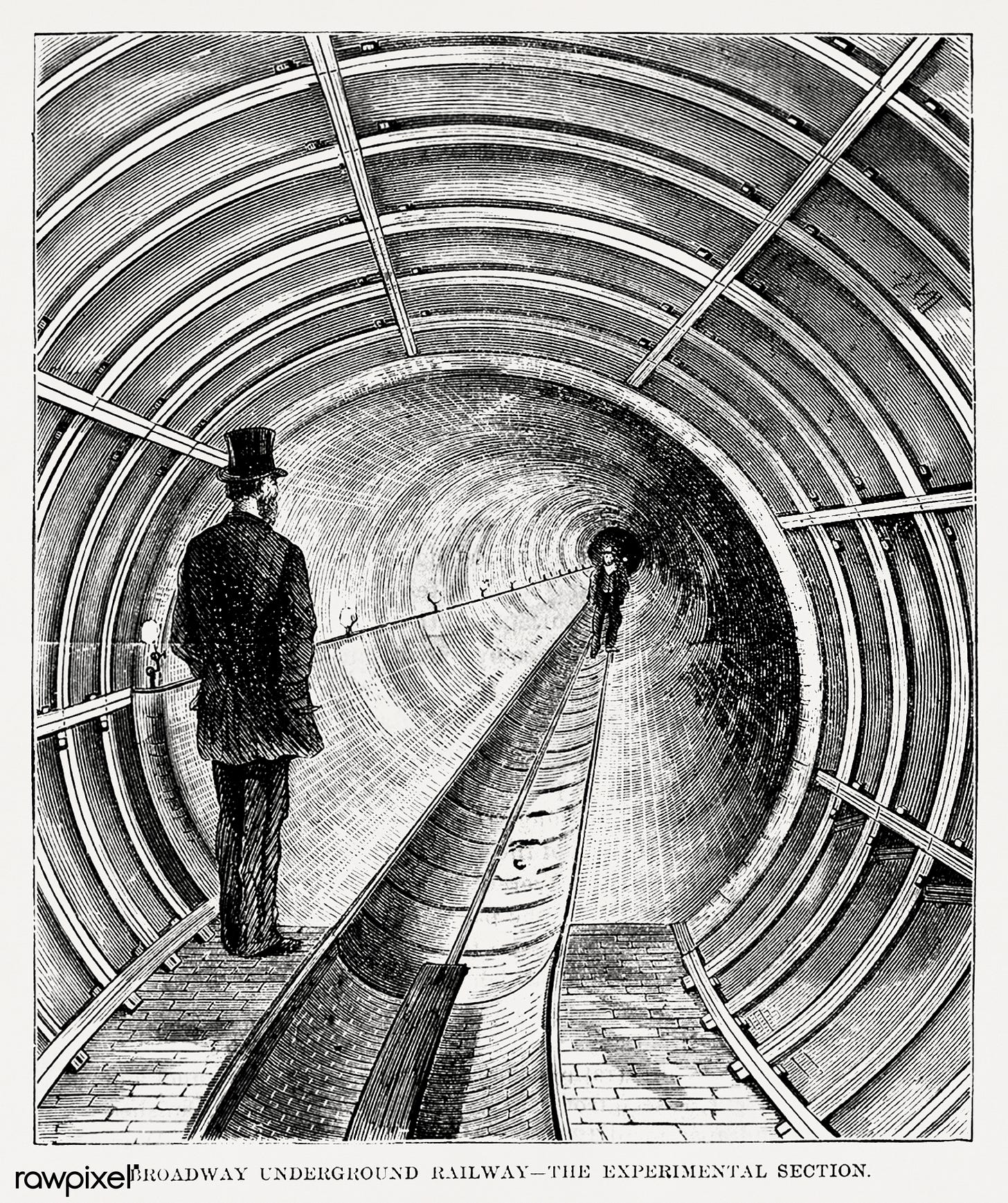

A far cry from the subway experience of today, this was Alfred Ely Beach’s vision for the future of public transportation in New York City. It was known as the “Beach Pneumatic Transit System”, a set of cylindrical railcars operating within an underground, vacuum-sealed tube, pushed along by positive and negative intakes of compressed air.1

In 1870, Beach’s Pneumatic Transit System was running a small, experimental line beneath Broadway. Twenty years later, it would be forgotten beneath the city streets, the abandoned relic of a bygone era.

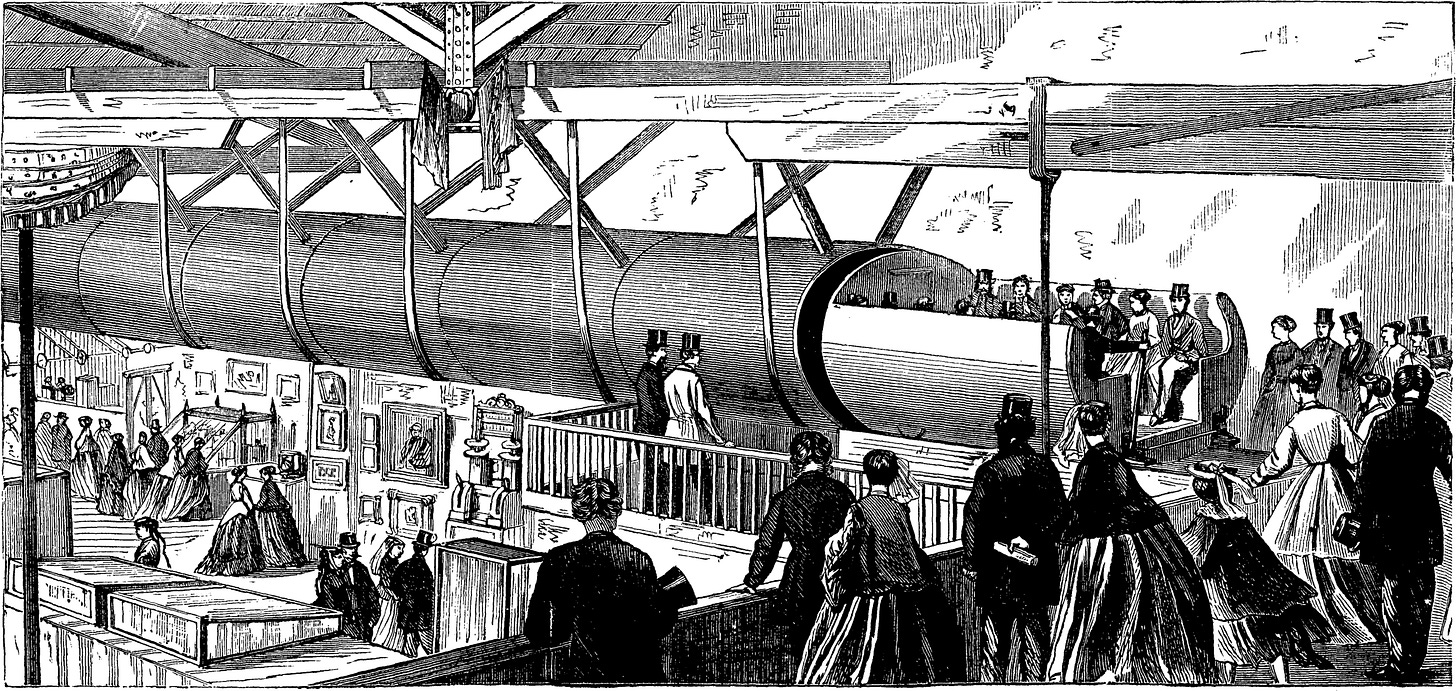

Beach first unveiled his plans for a pneumatic transit system before the American Institute Exhibition of 1867, one year before New York’s elevated railway began operation and four years before Alfred Speer suggested a moving sidewalk be constructed above the city. It was a time of unprecedented urban expansion, and the city was grasping at straws in an attempt to streamline public transport for its surging population.

References to pneumatic systems first appeared in the 1600s, and by the mid-19th century, many cities were using underground pneumatic tubes to move mail and parcels across town. Engineers had flirted with the idea of pneumatic public transportation as early as the 1810s, and in 1864, a single line opened as a tourist attraction in London’s Crystal Palace Park. In light of this, Alfred Beach believed pneumatic tunnels could bring New York City into the future.

A tube, a car, a revolving fan! Little more is required. […] No screeching whistles or jangling bells disturb the community, no turnpikes require to be guarded; there is no running down of the helpless, no mangling of passengers, no burnings from sparks; no fearful dangers of any kind […] [the passenger] reaches his journey’s end without injury to his apparel from these causes, and without having the complexion smutted with smoke.”

Alfred Ely Beach, “The Pneumatic Dispatch” (1867)

It wasn’t too difficult for Beach to get his foot in the door. By 1867, he had already amassed significant fame and fortune. The scion of a prominent Massachusetts family, he had spent the past two decades making a name for himself as a successful patent lawyer, working alongside the likes of Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas Edison, and Cornelius Vanderbilt. He was the co-founder of Scientific American, and even patented a few of his own inventions, including the first typewriter for the blind and a system for heating water with solar power.

With his well-established reputation—and near-unlimited spending money—it wasn’t long before the Beach Pneumatic Transit System became a reality. In 1869, crews broke ground beneath Broadway. Fifty-eight days (and $350,000) later2, a 300-foot tunnel was constructed between Warren Street and Murray Street, the project entirely funded by Beach’s personal fortune.

Had he obtained support from New York’s politicians, Beach may not have had to fund the project himself, but this was not the case. Broadway’s wealthy landowners strongly opposed any sort of unsightly construction within the vicinity of their buildings, so construction for the Beach Pneumatic Transit had to operate under subterfuge. The company claimed it would construct a tunnel twenty feet beneath Broadway in order to house “pneumatic postal tubes for the city”.

The project remained under a veil of secrecy until its grand opening on February 26, 1870, when Beach’s Pneumatic Transit System took its inaugural ride. A bewildered public entered the ornate station for the first time, passing through a series of vacuum-sealed doors into a wood-paneled reception room. They faced an enormous fountain in which goldfish swam back and forth, their bright orange scales shimmering beneath gas-lit chandeliers.

For 25¢, patrons could earn a plush seat within the luxurious cabin of Beach’s pneumatic passenger car3, where decorative lamps cast an amber glow on the paneled ceiling. When the conductor pulled a wire on the wall, the car was set in motion, reaching the opposite station in a matter of moments. In the first two weeks alone, Beach’s Pneumatic Transit hosted 11,000 passengers, with all proceeds donated to charitable organizations.

“Certainly the most novel, if not the most successful, enterprise that New York has seen in many a day is the Pneumatic Tunnel under Broadway,”

The New York Times, February 27, 1870

For three years, Beach’s Pneumatic Transit shuttled between Warren Street and Murray Street, enthralling hundreds of thousands of passengers and captivating the nation’s masses. When the time came to discuss the railway’s expansion along Broadway, Beach enlisted the help of William “Boss” Tweed, New York’s most influential (and corrupt) politician. Had this alliance been made three years earlier, Beach’s Pneumatic Transit may have still been in operation today. However, in 1872, this choice would lead to Beach’s eventual unraveling.

That year, Boss Tweed went down for larceny, and any hopes for the expansion of Beach’s Pneumatic Transit went down with him. For a year, Beach struggled to secure approval for further subterranean construction in vain. He would later claim that Tweed had undermined the railway’s progress, in an attempt to gain favor with reformers, but in the end public support and potential funds simply dried up. The Panic of 1873, which sent the Western world into an economic depression, was the final nail in the coffin. By the end of the year, Beach’s Pneumatic Transit closed its vacuum-sealed doors for good.

The tunnel’s entrance was sealed with a wall of brick, and the station was rented out as a multi-purpose space. The elevated railway, or “the El”, which also began operations in 1870, became Manhattan’s preferred form of public transportation. Two years after Beach’s death in 1896, the building above his station burned to the ground, destroying much of what was left in the opulent railway terminal.

In 1912, excavation for a new form of subterranean transit was underway—the New York City subway. Construction crews were tasked with clearing out the remains of Beach’s pneumatic tunnel to make way for subway lines. In doing so, they uncovered an intact passenger car, the station’s grand piano, and the tunneling shield Beach had invented, artifacts from a forgotten time in New York’s history.

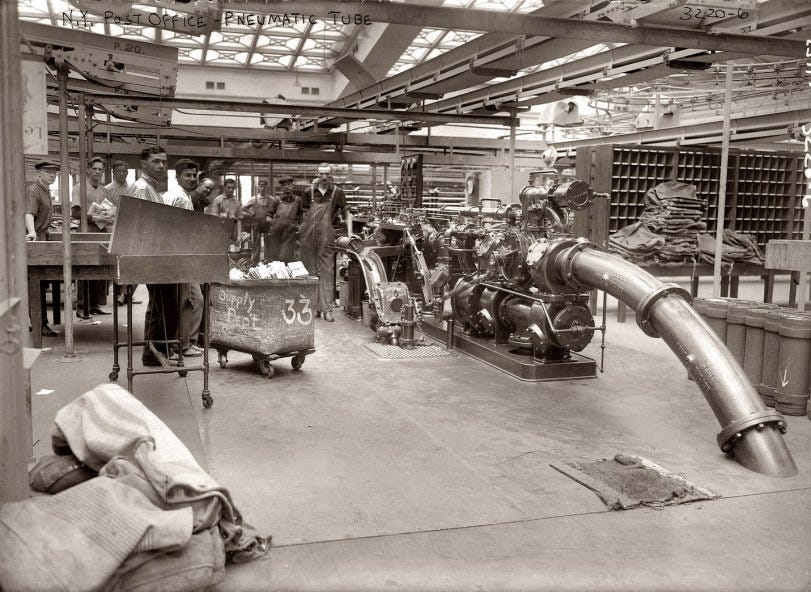

All said, Beach’s legacy in New York was not completely lost; in an ironic twist, his 1869 cover-up became a reality. One year after his death, New York City’s postal service adopted a pneumatic system for delivering mail, installing miles of underground tubes across Manhattan. These pneumatic tubes were used for postal deliveries until 1953, and many still exist beneath the city today.

Pneumatic systems have largely been replaced by newer technologies, but that hasn’t diminished their allure. In the late 1960’s, engineers at Lockheed Martin toyed with the idea of a 400-mile long pneumatic railway connecting New York and Washington D.C.. Since 2013, Elon Musk’s SpaceX has promoted concepts for the “Hyperloop”, a high-speed, air-powered train operating under the same principles as Beach’s Pneumatic Transit System.

As of 2025, pneumatic public transportation has yet to enjoy its time in the spotlight. For now, a plaque honors Alfred Beach in City Hall station, marking the former location of his railway tunnel and recognizing his influence in the development of New York’s current subway system. This seems to be the only physical reminder of Beach’s Pneumatic Transit System left—everything else has been lost to fire, construction, and human error. Today, all that remains is the story of the ultra-modern transit system that never was.

As always, thanks for reading extracurriculars! For more deep dives, obscura, & niche history like this, consider subscribing below.

For more, check out these resources:

Beach Pneumatic by Joseph Brennan is an insanely detailed account of the rise & fall of Beach’s Pneumatic Transit System. This webpage was formerly hosted by Columbia University and is now available in the internet archive.

Alfred Beach’s Pneumatic Dispatch from 1867, detailing his ideas for various pneumatic applications is available in the public domain.

This reddit thread details u/Blakey02’s exploration of the underground area once reserved for Beach’s pneumatic railway. A small portion of the pneumatic tunnel is still visible, but everything else has been destroyed or lost. The pictures & thread are fairly interesting and worth checking out!

In this scene from Ghostbusters II, the crew discovers a river of slime flowing through an abandoned pneumatic tunnel beneath NYC. The tunnel is clearly a replica of Beach’s, and the movie even nods to an 1870 completion date.

It all feels a little space-age meets steampunk, but this is the same technology we still see in use at the bank drive-thru today.

$8.5 million in 2025

About $6 today—this was a hefty price to pay for a short ride, but at the time, the Beach Pneumatic Transit System was more of an attraction than a true public transport system.

Very interesting thank you for this!

Fascinating!!