The Record Keepers

the stories of ordinary people, memorialized by the "scraps" they left behind

Scholars and archivists sometimes joke that scrapbooks are hardly “books” at all. They are objects: blank journals, sheet music compilations, and old ledgers stuffed with an abundant variety of personal materials, from photographs and pressed florals to news clippings, coins, and locks of hair. Their subject matter typically has no rhyme or reason; it is unlimited, as varied as the creators of the scrapbooks themselves.

For this reason, scrapbook archival is a notoriously complicated business. Their wide array of ephemera, paired with copious inks and adhesives, make preservation a laborious and often multi-disciplinary enterprise. But perhaps this messy, complicated reputation serves as the perfect metaphor for the multifaceted human experience scrapbooks are meant to represent.

When scrapbooking emerged in the early-to-mid 19th century, it gave ordinary people the ability to memorialize their lives in ways they never had before. History was no longer reserved for the educated, the wealthy, and the powerful. Personal legacies were no longer limited to oral histories, diaries, or handwritten lists at the back of the family Bible. With some adhesive and a pair of scissors, anyone could tell their story—complete with the keepsakes, photos, and relics that defined them.

Below are selections from five historic scrapbooks available in the public domain. Their pages preserve the lived experience of individuals who might otherwise be lost to time, everyday people turned documentarians, archivists, and conservators of culture and tradition. The things they left behind seem to reflect the fundamental qualities of human nature that transcend the passage of time.

To Ysidora: A Father’s Scrapbook for his Only Daughter

On November 18, 1898, Henry and Rosalie Louis celebrated the birth of their first child, a daughter named Ysidora. As is common in the Jewish tradition, she was named for her late grandfather, Isidor, who had passed three years prior.

Henry and Rosalie created a scrapbook for Ysidora, saving all sorts of memorabilia from her first years among Los Angeles’ nascent but flourishing Jewish community: crafts, photos, invitations to children’s parties and Purim balls. But tragedy struck in 1902, when Rosalie died unexpectedly.

While making a name for himself as a key player in the apparel industry, Henry continued to raise his daughter—and keep her scrapbook—on his own. His love for his daughter and his pride in her accomplishments are evident throughout. Today, Ysidora’s album gives us an uncommon glimpse at Jewish girlhood in the early 20th century.

Ysidora’s artwork is my favorite part of the scrapbook. Childhood fantasies, trending fashions, and life in early 1900’s Los Angeles come to life in her creations.

The latter parts of Ysidora’s album appear to show her own efforts at scrapbooking, with hand colored clippings of well-dressed ladies adorning the final pages. The book seems to have been completed around 1908, but it wasn’t acquired by the Jewish Historical Society of Southern California until the 21st century. You can view it in full here.

Control Amidst Chaos: A Teenager’s WWI Scrapbook

When Alice Deacon was 17 years old, it seemed like everyone she knew was shipping off to war. Records indicate that at least two of her three elder brothers were enlisted in the service by 1916. According to the scrapbook she began that year, so were many of the boys from her neighborhood.

Alice’s scrapbook appears to have been a sort of coping mechanism, as many of its pages are dedicated to keeping tabs on local young men fighting overseas. It’s possible that scrapbooking gave Alice some sense of control during a traumatic and unpredictable time.

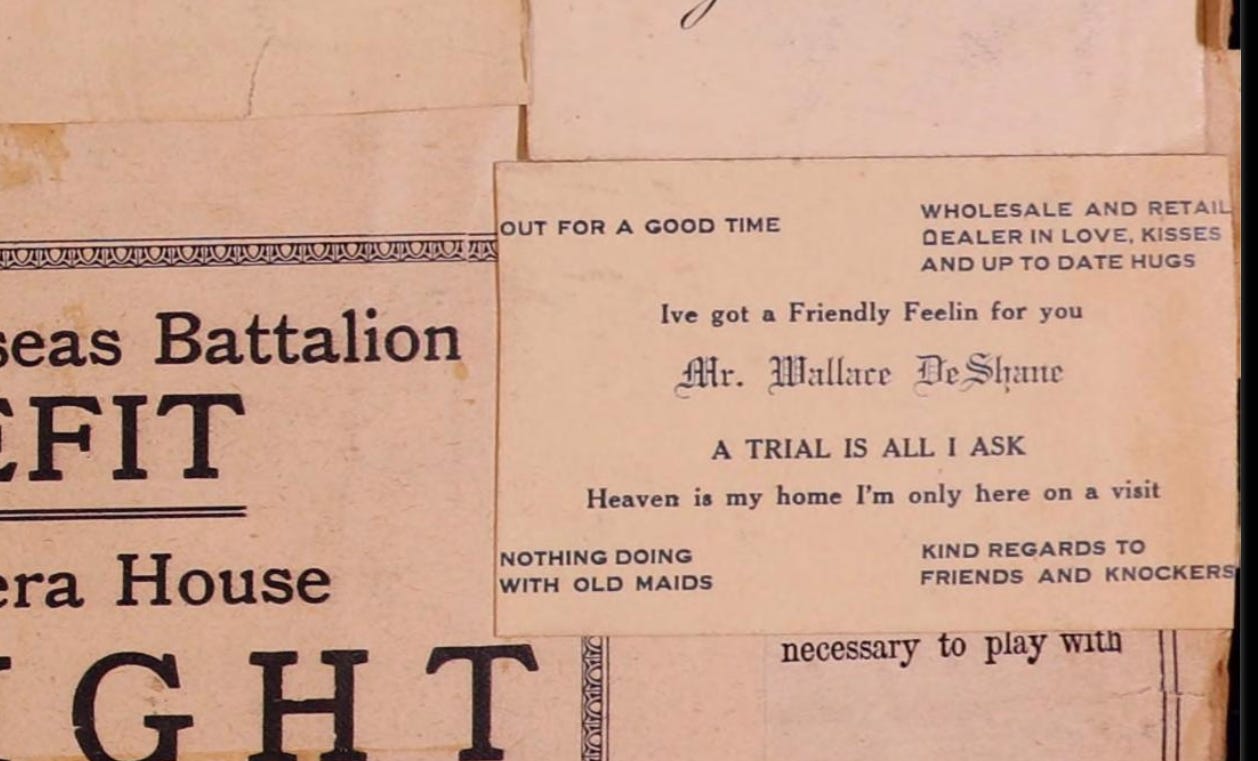

Though blank scrapbooks were available for purchase at the time, Alice used a book of piano-forte sheet music from 1859 to compile her clippings. Could this reflect a sort of urgency in the album’s creation, or it is instead an example of careful budgeting during wartime?

One of the first pages in Alice’s scrapbook is dedicated to the tragic story of Sgt. George E. Turner, who sent a poem to his young son, Billy, shortly before being killed in action. The poem is devastating, and must have struck a chord with Alice.

Along with clippings detailing the injuries and deaths of soldiers from her hometown, Alice used pictures from the local high school to keep track of those she was acquainted with. Above, she notes that boys marked with a red “X” are dead.

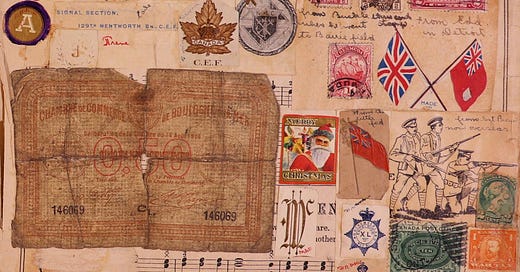

At the turn of the century, “calling cards” were exchanged as a way of maintaining social bonds, and many scrapbookers saved them as a token of friendship. In 1916, Alice marked them to remember her friends’ military units. I can’t help but wonder whether the Christmas card at left reflects Alice’s hopes for her loved ones overseas.

A trial is all I ask! Wallace DeShane deserved an honorable mention.

A few pages in Alice’s scrapbook are sprinkled with wartime ephemera: stamps, illustrations, banknotes, and chocolate wrappers. On one page, the remains of pressed flowers “from a ruined French village” can be seen. These pages are a perfect example of the immersive quality of some historical scrapbooks; the reader is surrounded by the ordinary objects of a bygone era.

Census records indicate that all of Alice’s brothers survived the war. In 1929, she married a veteran named Leo Houlihan and the two had one son. Sixty years after Alice’s death in 1955, her scrapbook arrived at Belleville’s Community Archives. The full text is now available here.

“The Madame B Album”

Many men kept scrapbooks; Frederick Douglass, for example, famously kept many to record the promises and failures of Reconstruction. But scrapbooking is still typically classified as a “women’s hobby”, and for this reason it has historically been regarded as a lower art form, perhaps even “emotionally motivated amateurism”. To this day, the majority of scholarly research on scrapbooking is undertaken by women, and as Jennifer M. Black writes in her article Gender in the Academy, much of this research “seems to be devalued in the same way that the objects themselves were in the past”.

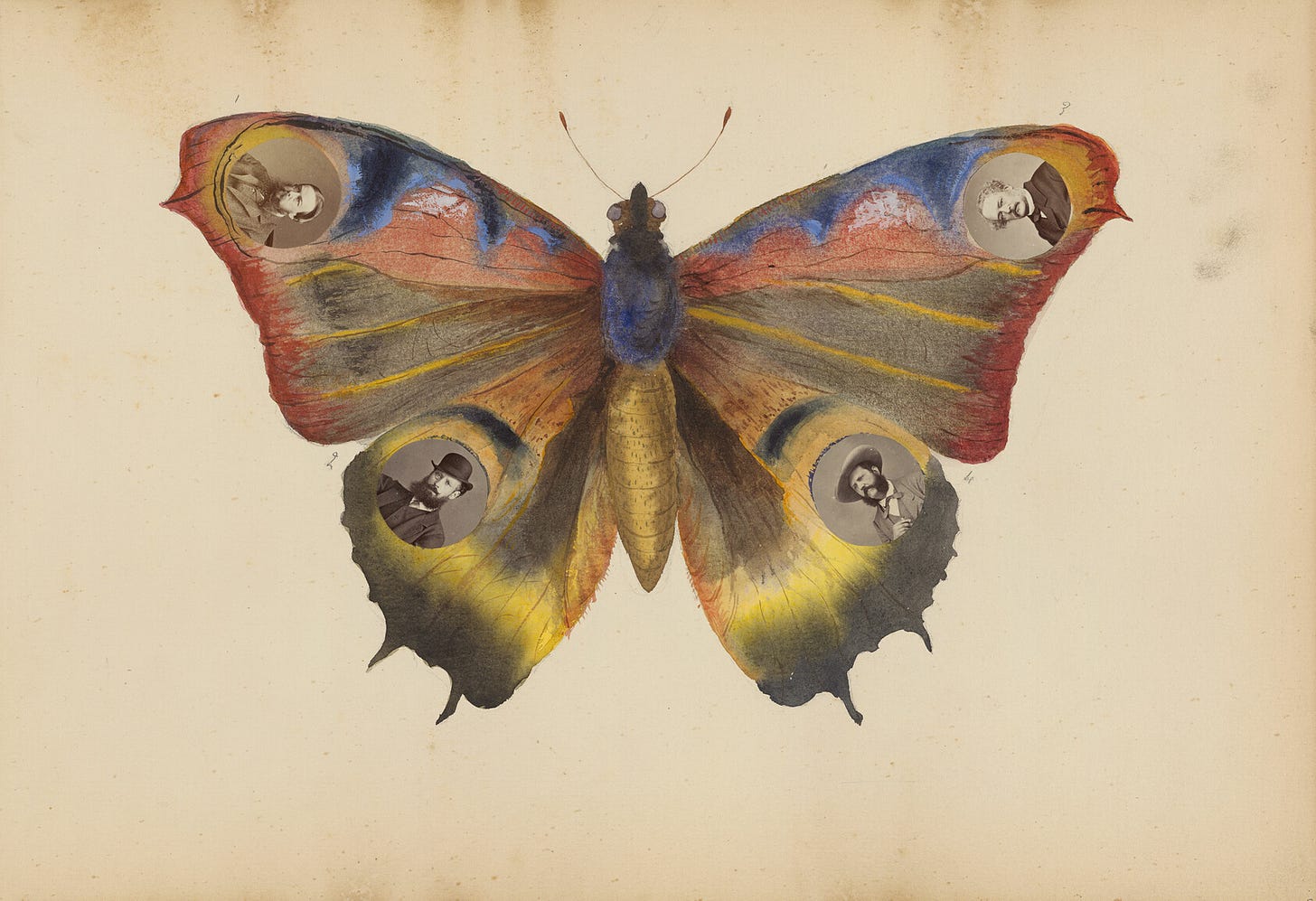

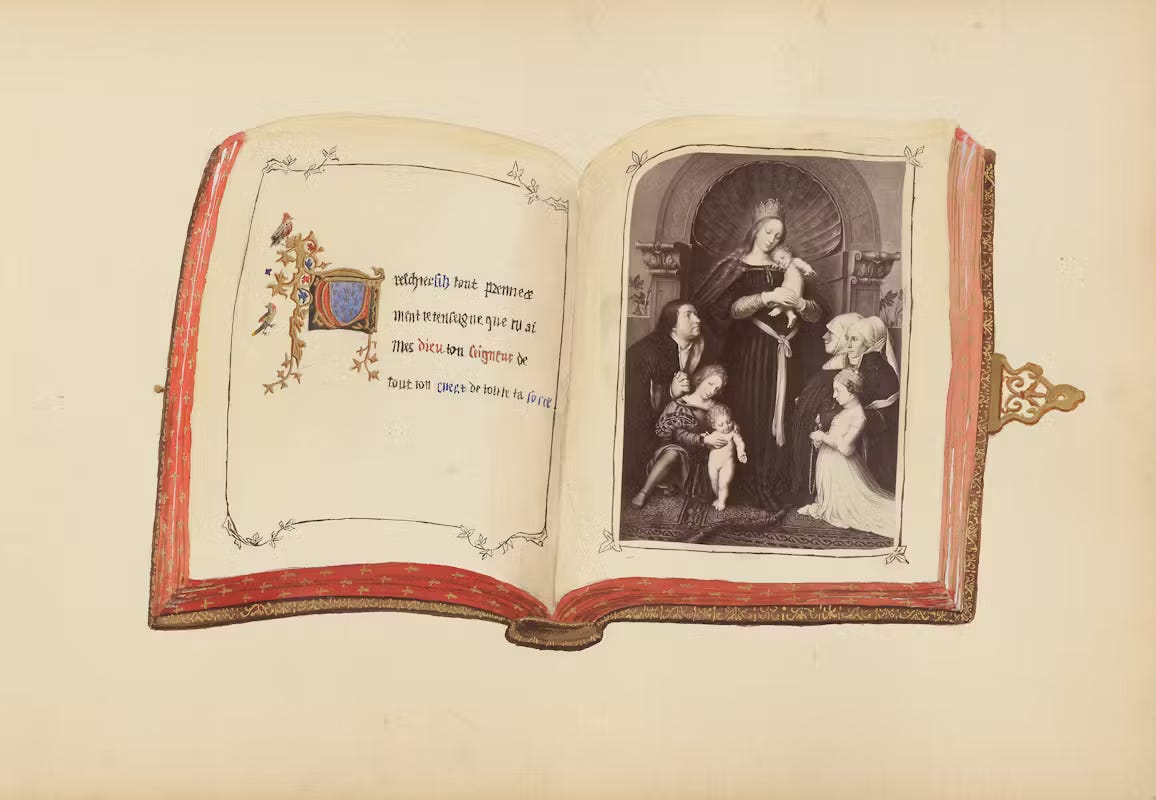

But many of the photocollage albums from the Victorian heyday of scrapbooking are true works of art and deserve recognition as such. Their breathtaking composition, subtle messages, and meticulous detail is epitomized in “The Madame B Album”, an 1870’s scrapbook attributed to Marie-Blanche Hennelle Fournier, known in life simply as “Blanche”.

Madame B’s scrapbook is not only an incredible work of art, it is also a rare find. Blanche was a Frenchwoman, and these types of albums were made “almost exclusively” by the upper-class women of England. From this information, and from the details of Blanche’s artwork, archivists have made inferences about the woman behind the album:

As the second wife of a diplomat, [Blanche] may have used her album to help establish herself and her family within a specific social set or to demonstrate her role as a new wife. The album may also have functioned as a sort of travelogue, depicting places she visited or was stationed with her husband. The painted elements reveal that the maker of the album was knowledgeable about the artistic styles of various cultures and skilled in botanical and zoological drawing.

Blanche left many parts of her scrapbook unfinished. It seems that at some point, she lost interest in its completion. During her life, she likely shared her work with the women of her social circles, and it is almost certain that this is where she thought its circulation would remain. A century later, however, her work can be viewed at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Historic Black Asheville in Annette Pearson Cotton’s Scrapbook

Before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 began the slow process of integration in the southern U.S., Black entrepreneurs and civic leaders took it upon themselves to offer Black Americans the kinds of social and economic opportunity they were barred from. One such leader was E. W. Pearson, a Spanish-American War veteran whose numerous business ventures helped him cultivate the Pearson Park neighborhood of West Asheville, North Carolina.

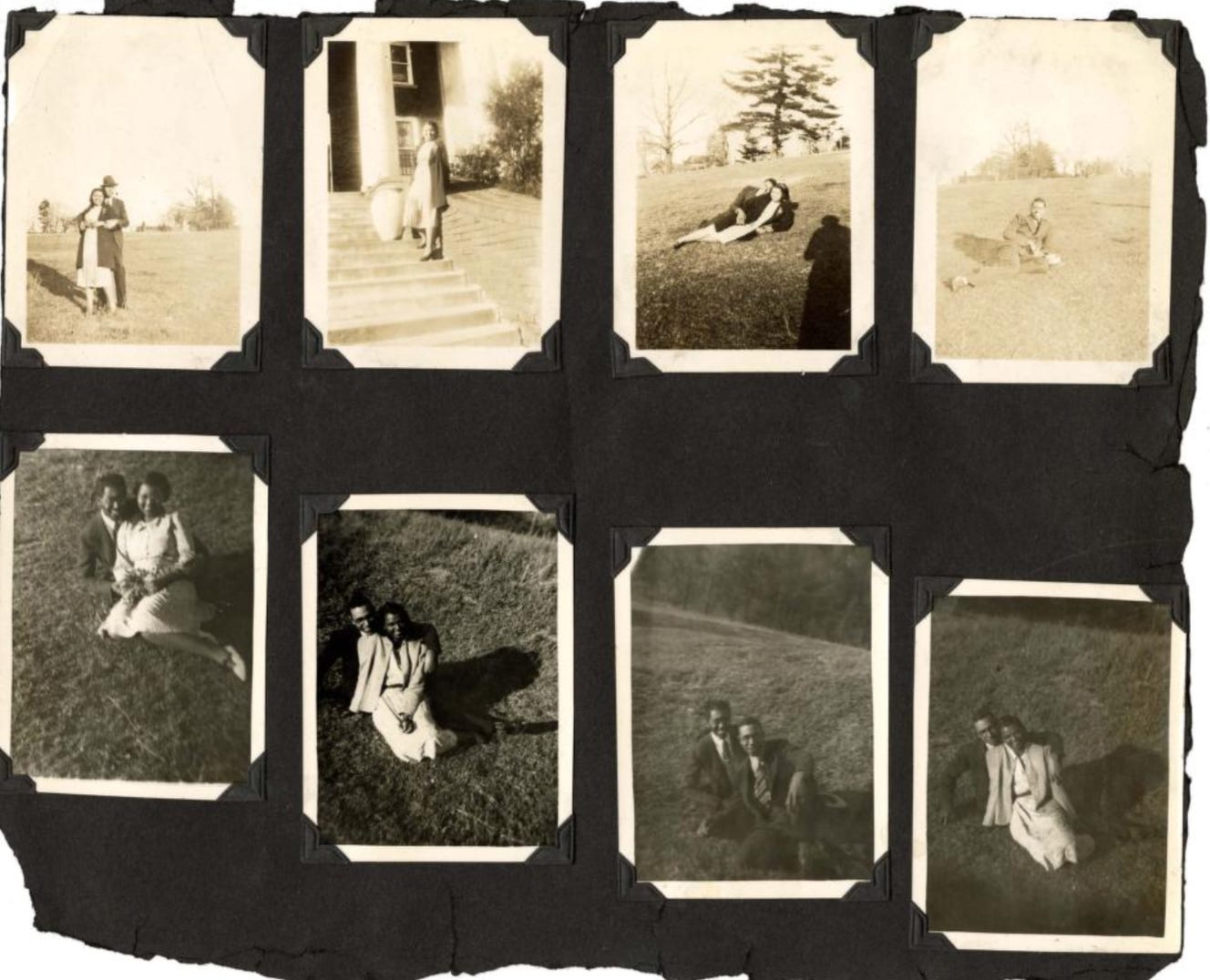

Pearson invested millions of dollars into his community. He opened a grocery store, organized an annual agricultural fair, and even assembled Asheville’s first semi-professional African American baseball team. His daughter, Annette Pearson, kept a scrapbook documenting her life as a young woman, wife, and mother in Pearson Park. Her casual, dreamy photos depict the rich history of the South’s early 20th century Black communities.

Annette married Clifford W. Cotton in March of 1942, when she was 25 years old. The pictures above are likely a mixture from their two families.

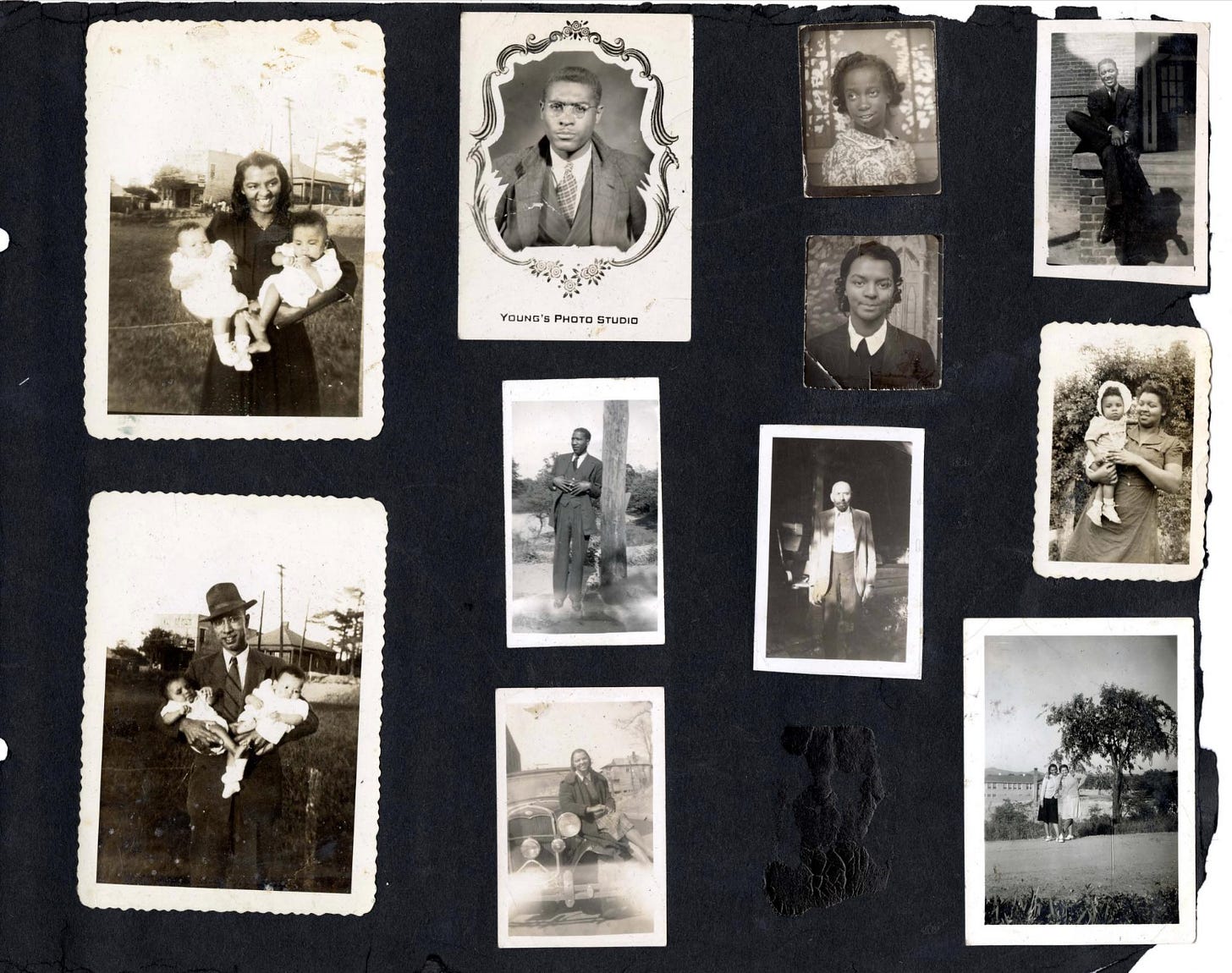

A year later, Annette and Clifford welcomed a son, Clifford Jr., to the world. Annette’s love for her son and husband shines through the pages of her scrapbook; their pictures are found on almost every page. The young family is pictured above, at bottom left, one month after Clifford Jr. was born.

Above, E.W. Pearson and his wife, Annis, are pictured during a visit with their grandchildren. E.W. Pearson would pass away in 1946, a few years after Annette began keeping her scrapbook.

Annette and Clifford lived in Asheville for the rest of their lives. She passed away in 1997 at 90 years old. Though her neighborhood is no longer known as Pearson Park1, her father’s Asheville legacy lives on. The agricultural fair he organized still takes place every year, and a mural in his honor graces the facade of the Burton Street Community Center. In 2019, Annette’s son donated her scrapbook to the Buncombe County Library. It is now in the public domain, and can be viewed here.

The Many Adventures of Bunny & Rita

In 1955, Nancy ‘Bunny’ MacCulloch and Rita Charette packed up their lives and traveled from Connecticut to Los Angeles, California. There, they would spent the next decade of their lives working, traveling, and enjoying the company of their friends and cats. The two were barely 20 years old.

Bunny and Rita were an openly gay couple at a time in U.S. history when homosexuality was still considered a crime. Their scrapbook, compiled by Bunny, documents the joys and struggles of life in the LGBTQ+ community of mid-cenutry America.

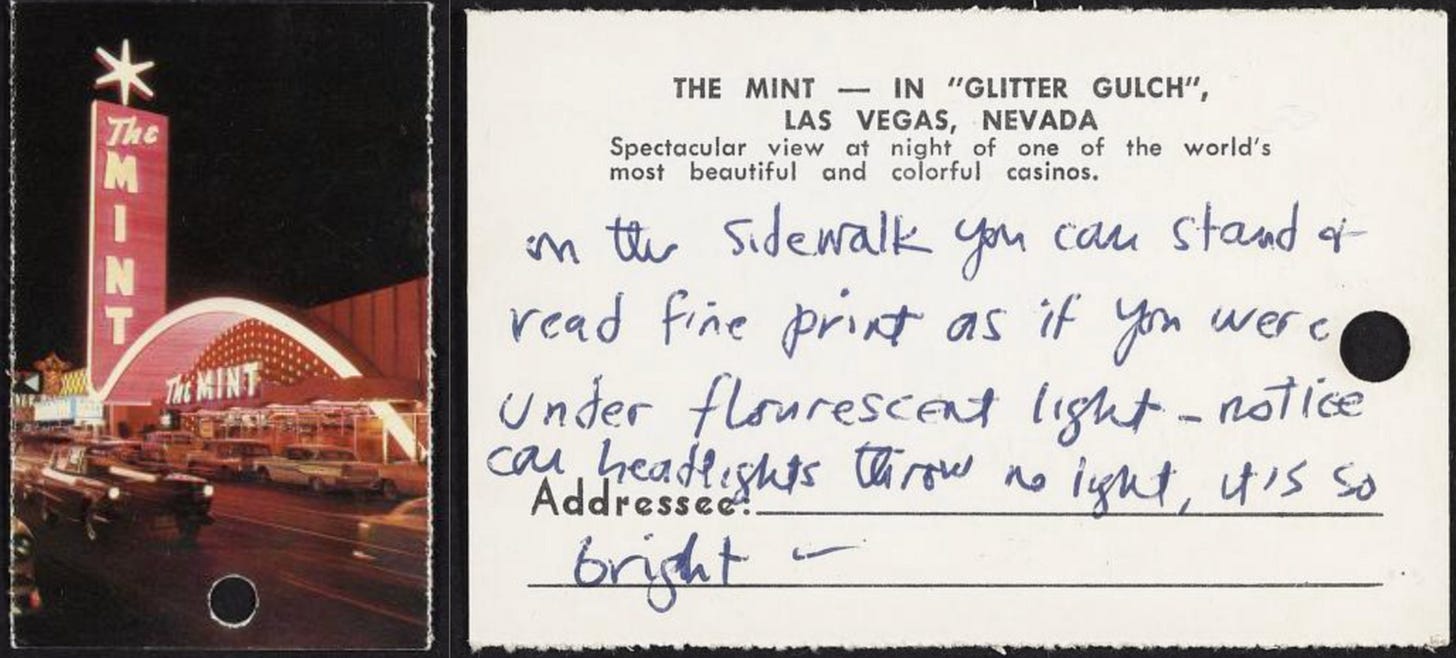

Bunny’s scrapbook begins with hers and Rita’s cross country journey, documenting their sights and experiences.

Above, Bunny and Rita are pictured at left, celebrating Christmas 1959. In her private life, Rita’s dress and presentation were more masculine. In her public life, this was not an option, seen below as she prepares for a trip to San Francisco.

Many of Bunny and Rita’s friends were members of the LGBTQ+ community, and their stories are also documented throughout the scrapbook’s pages. We don’t usually get to see the queer community of this era portrayed in such a casual, candid light.

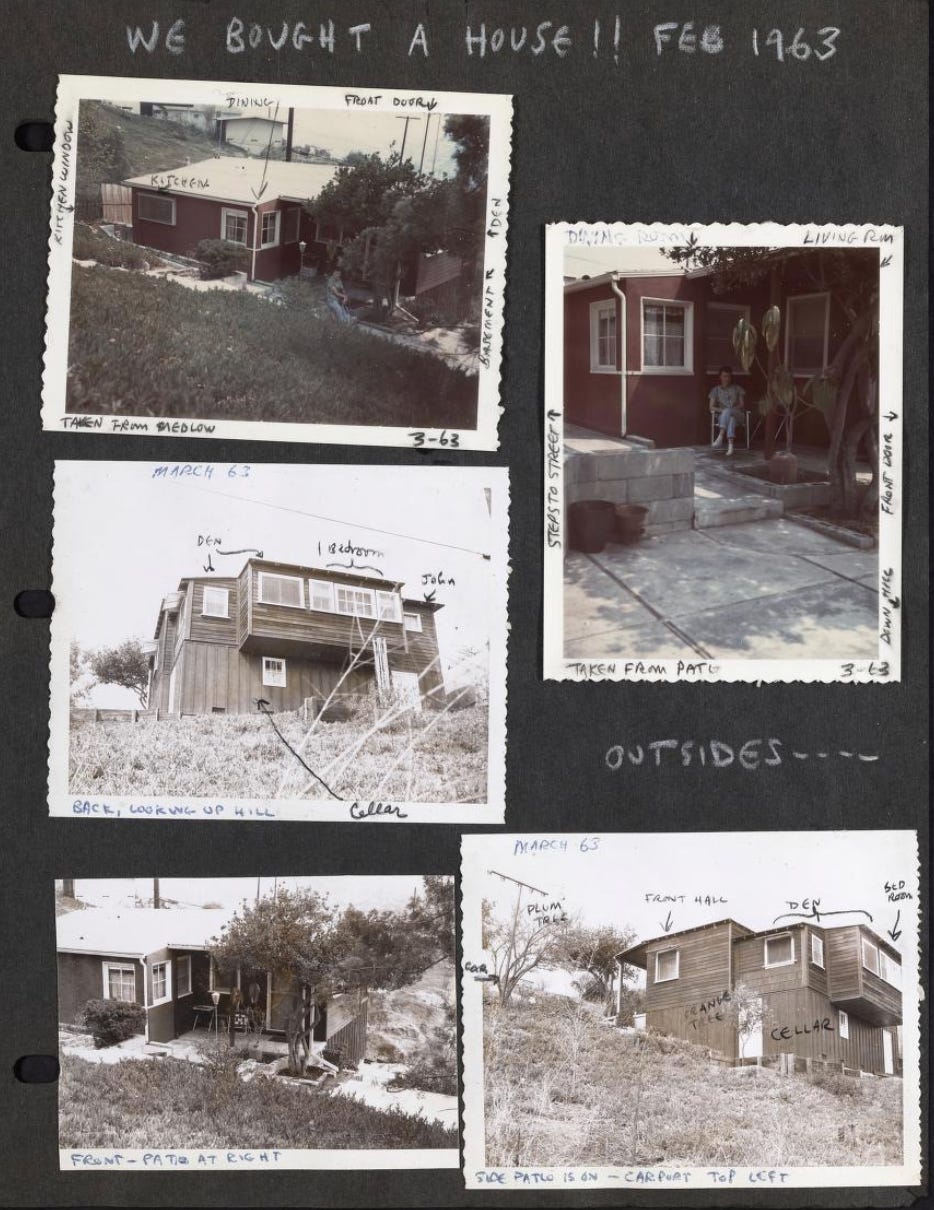

In the early 60’s, Bunny and Rita purchased a laundromat, which they owned and operated together until their breakup in 1965. This wasn’t the end of their story, though. The pair would rekindle their relationship in 1974. Though they would eventually part ways for good in 1977, Bunny held onto all their scrapbooks and memories.

Rita would go on to work in biomedical engineering, and a closer look at her story can be found here. Until her death in 1989, Bunny devoted her life to the preservation of lesbian history. Her scrapbooks are still available to view (1955-1965, 1974-1979) thanks to the efforts of the June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives, named for her late partner.

If not for the scrapbookers, the archivists, and record keepers of ordinary life, who would tell the stories of everyday people? Would we know about the poem Billy’s father wrote from the Western Front, or that primrose and violet still bloomed among the ruins of French villages? Would we remember Madame B’s immense talent, or Bunny and Rita’s laundromat?

Human history is skewed towards the world leaders and the war heroes, the fraction of the population whose actions defined the course of history but whose lives hardly represent the vast human experience of the past. The diverse and complex stories of those who witnessed the tumult of our history books are rarely shared—unless of course, we preserve them and pass them down.

For decades, a dozen worn scrapbooks occupied a shelf in my grandma’s basement closet. When you yanked the door open, its hinges creaking in defiance, the spines stood out to greet you, bound in green canvas, red and brown leather, and groovy midcentury florals.

As a kid, I would pull them down one by one, carefully examining the time-worn pages of my family’s story. Sometimes, my grandma sat beside me to fill in the blanks between the pictures, sharing the bits of our history not scribbled into the margins. My grandma is 90 today, and her scrapbooks now occupy a smaller shelf in her new apartment. But sometimes we still sit side by side, an album across our laps, revisiting the stories of our shared past.

As always, thanks for reading extracurriculars! For more deep dives & niche history like this, consider subscribing below.

For more historical scrapbooks, check out the links below—and prepare to waste an entire afternoon!

Kathleen Cridge’s high school scrapbook details life at Coronado High in the early 20’s. Kathleen was a drama student and a social butterfly, and her scrapbook is filled with candid photos, playbills, and high school sports reporting.

Annie Whelen Jensen’s scrapbook focuses on her two loves: her restaurant, the Tailgate Cafe, and trucking. Annie owned the Tailgate Cafe during the mid-20th century and collected all sorts of truck-related ephemera, in her real life and between the pages of her scrapbook.

Walter Hart’s scrapbook documents his career as “a female impersonator” at a nightclub between the 1930s and 1950s. The term “drag queen” wouldn’t emerge until the end of Walter’s career, but his scrapbook makes it clear that his impressive career paved the way for the drag queens of the latter 20th century.

Helen Thoreau's anti-slavery scrapbook is a surviving example of the scrapbooks kept by abolitionists during the early-to-mid 19th century. In an attempt to keep news stories straight and keep track of the anti-slavery movement’s progress, abolitionists were encouraged to keep scrapbook records. Helen Thoreau kept many, and this particular scrapbook dates around 1813.

The Winterthur Library Digital Collections’ collage albums, or scrapbook houses, offer an unparalleled look at Victorian interior design. Their creators, who remain mostly anonymous, pieced together wallpaper samples, magazine cutouts, and fabric swatches to design rooms both real and imagined.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2010 exhibition of Victorian photocollage, organized by The Art Institute of Chicago, displays “Madame B’s” ornate work alongside that of other female scrapbookers of her time. A slideshow of the pieces can be viewed here, and information about the exhibition is available here.

Today Pearson Park is known as the Burton Street neighborhood

love this sm!

Fascinating! Loved the focus on different types of scrapbooks, and that list at the end is going to be so much fun to work through.