The Secret Photographs

travel through time via the hidden lenses of Carl Størmer & Walker Evans

Stare. It is the way to educate your eye, and more. Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something. You are not here long.

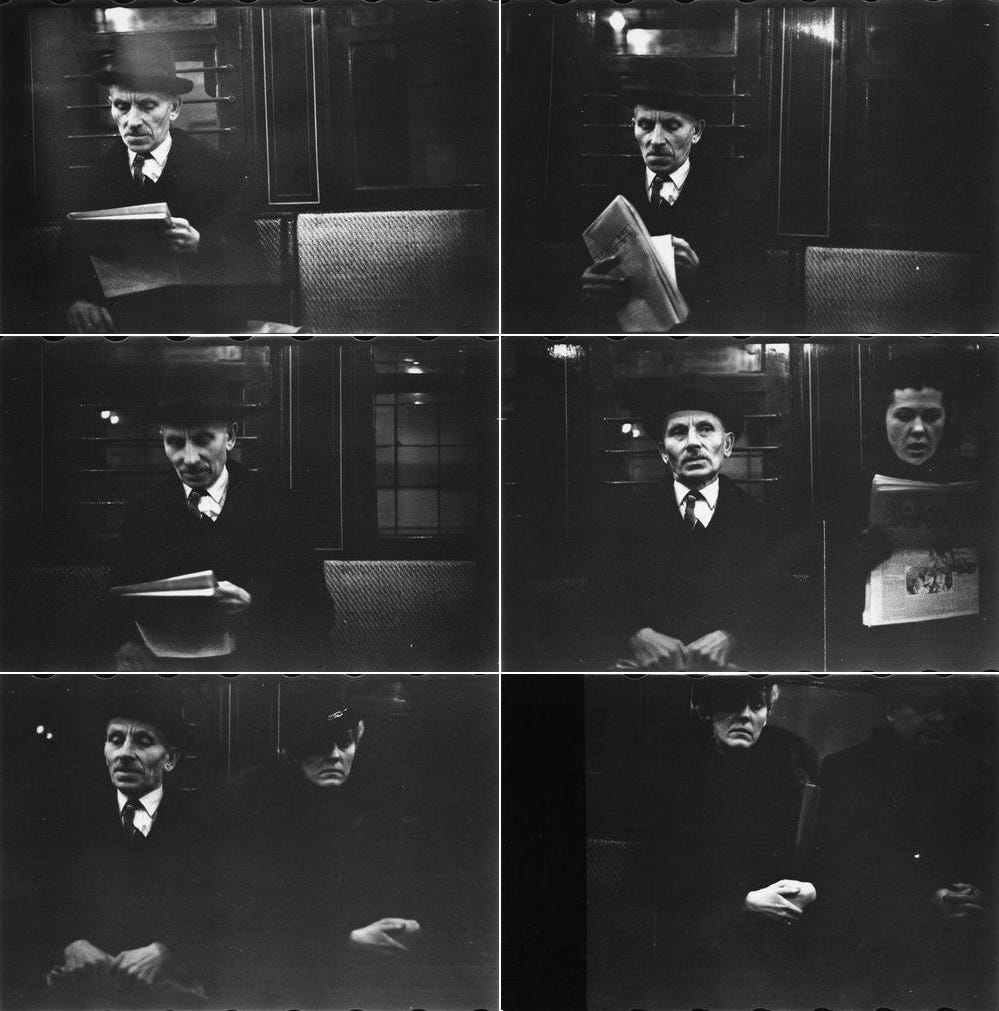

Walker Evans

Two men, separated by 3,500 miles and nearly half a century, stand before their mirrors. One man eyes his reflection in Oslo in the 1890’s, the other in 1930’s New York City.

Carl Størmer is barely twenty, preparing for his morning classes at the University of Oslo. He is studying to become a mathematician. Someday, a crater on the far side of the moon will share his name.

In 1938, Walker Evans is in his mid-thirties and is already well-established as a photojournalist. He has spent the last few years documenting rural poverty for the United States government. His work will one day define a generation.

Though separated by time and space, both men linger before their reflections, carefully examining their clothing before emerging into their respective cities. They pay close attention to their buttons, the seams of their shirts and coats. As it turns out, each man has hidden a camera against his chest, the lens covertly protruding from beneath layers of fabric.

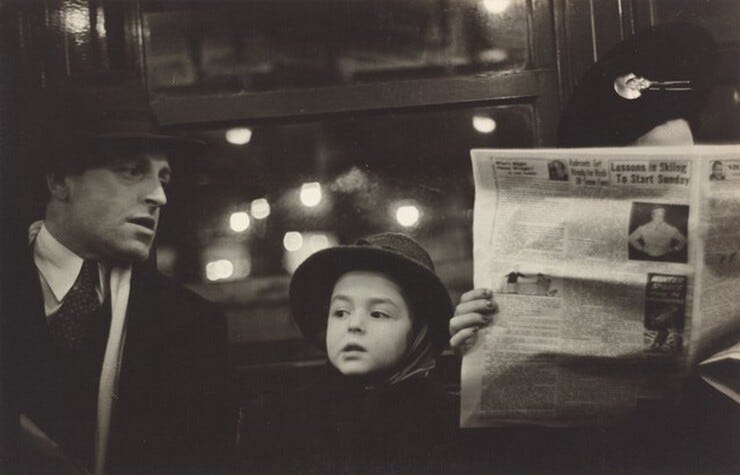

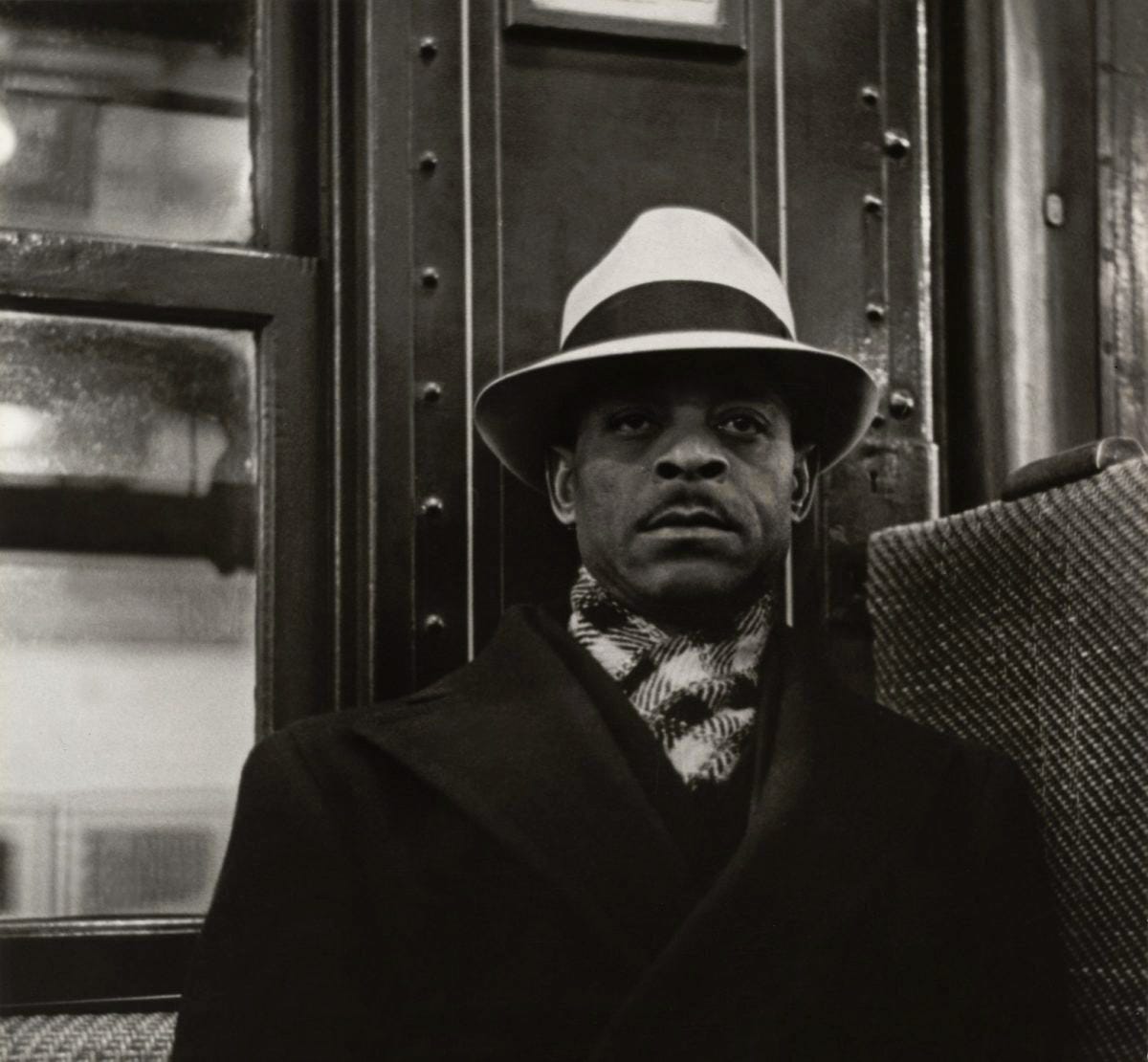

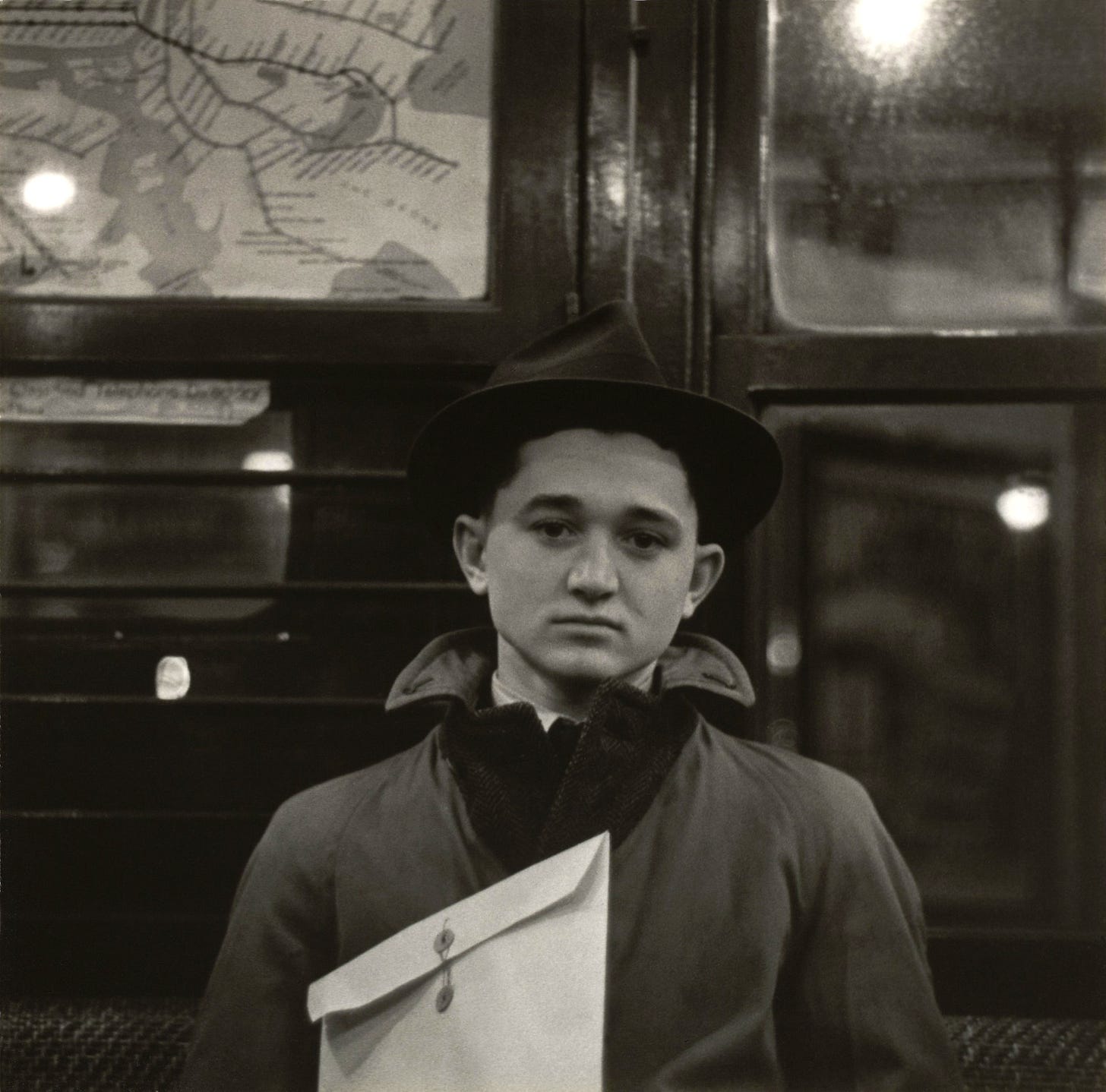

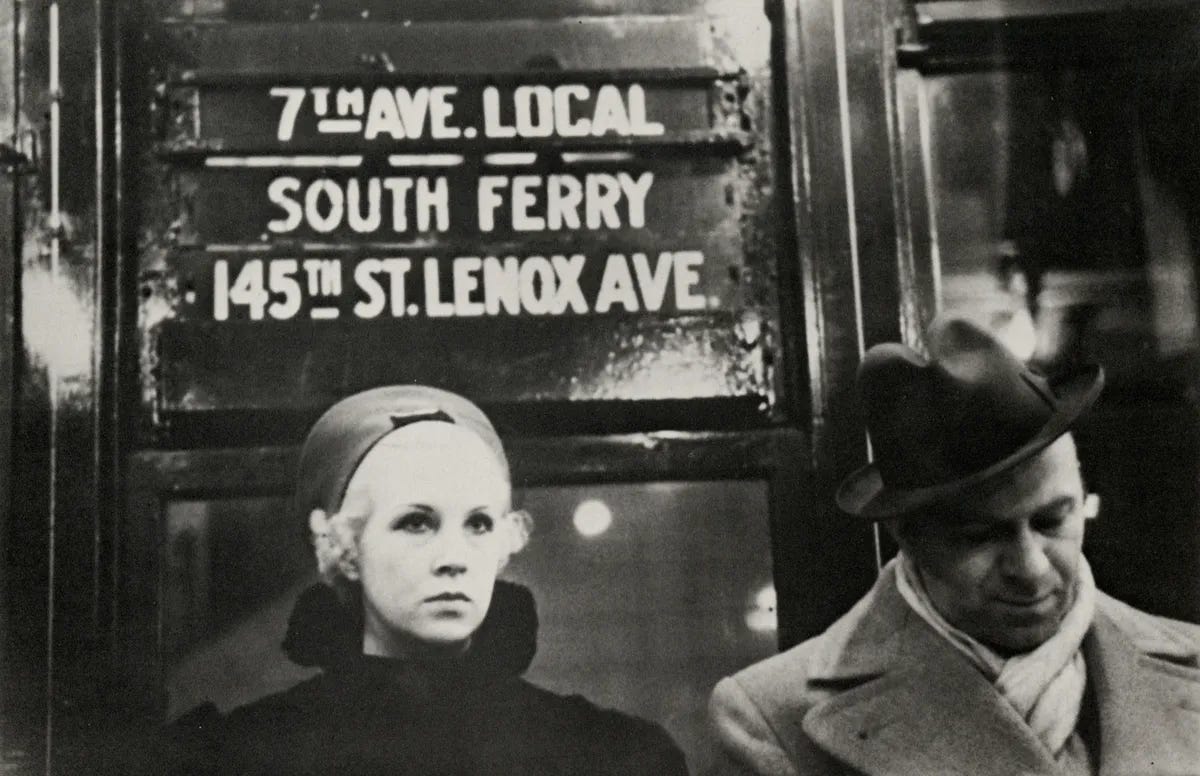

Combined, Carl Størmer and Walker Evans would take over 1,000 secret photographs of the world as they saw it, captured through the lenses they hid beneath their suit jackets and vests. A century later, these photos offer us an unparalleled glimpse at those who inhabited the past, people whose poses and expressions feel uncannily similar to our own.

We often imagine those who came before us to be more restrained, stiff, and solemn, but this assumption has a lot to do with the portraits they left behind. In the century following photography’s inception, being photographed was, for the most part, an infrequent and formal affair. Portraits typically involved a professional studio, a charming backdrop, and an assortment of calculated poses — and the resulting photos were often some of the only images one had of themselves. Rarely did these portraits demonstrate the personality of the subject. For those of us lucky enough to possess family photos from this time period, hardly any capture what our ancestors looked like when they smiled.

Though some argue that Størmer’s and Evans’ hidden-camera portraits are an invasion of privacy, images snapped without their subject’s consent, their photos have nevertheless made history as a uniquely life-like view of the past, virtually unattainable in any other artistic medium. They offer future generations a refreshing departure from the rigid, posed styles of the 19th and early 20th century: their subjects are wistful, tired, contemplative, and chatty. They are people who worked, loved, and suffered in the same ways we do, strangers whose intricate stories we will never know. But from centuries away, we can observe them as their authentic selves, as they were when they thought no one was watching.

They are members of every race and nation of the earth. They are of all ages, of all temperaments, of all classes, of almost every imaginable occupation. Each is incorporate in such an intense and various concentration of human beings as the world has never known before. Each, also, is an individual existence, as matchless as a thumbprint or a snowflake.

James Agee, Many Are Called

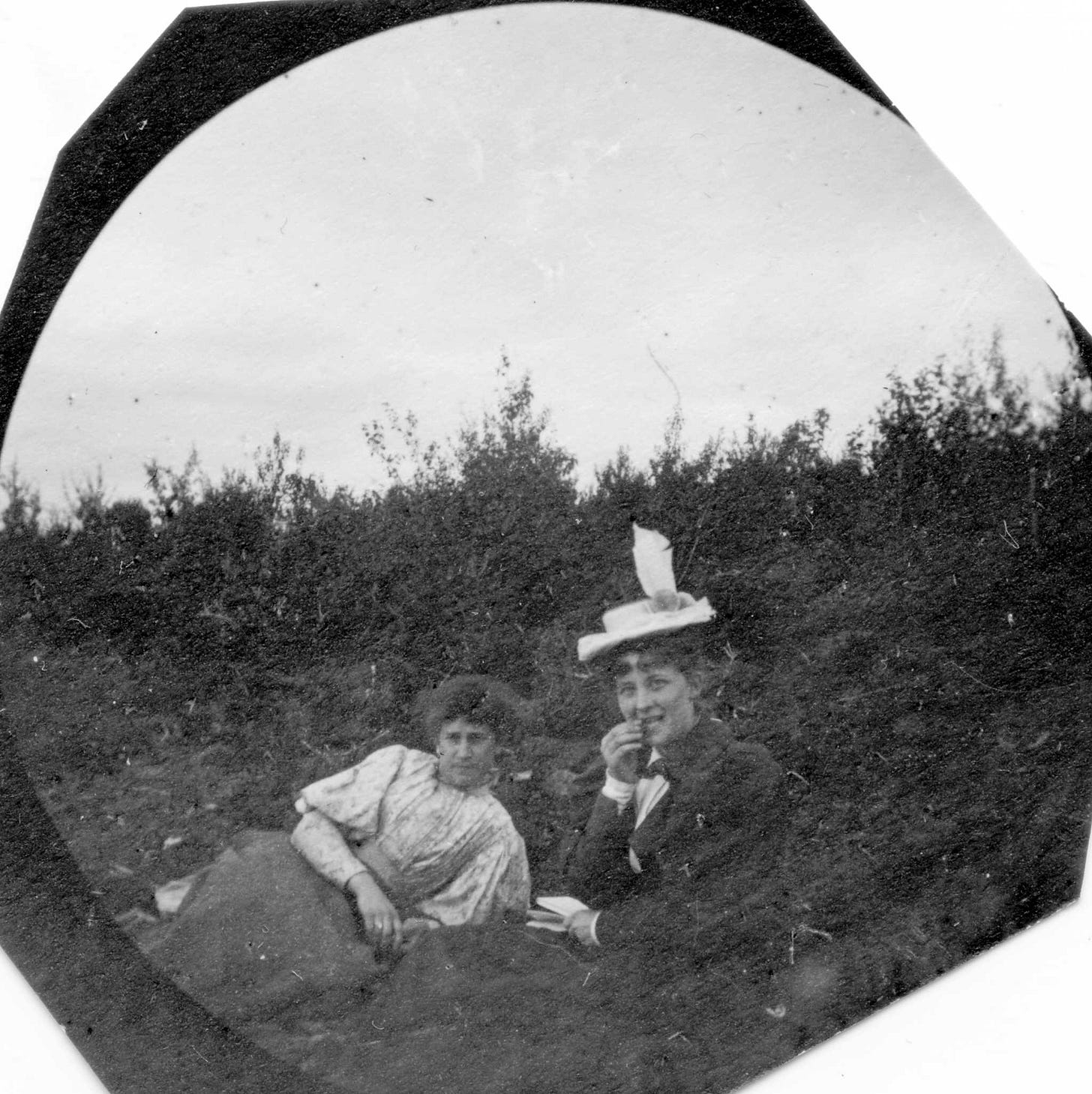

Carl Størmer was, admittedly, not a photographer. At least not by trade. He had just turned twenty and was studying mathematics at The University of Oslo. He only started using his C.P. Stirn Concealed Vest Spy Camera1 because he liked a girl. He was too shy to talk to her, but if he could just take her picture…

Though Størmer’s four-year portrait series began as a semi-stalkerish, lovestruck endeavor, it would produce some of the most authentically natural portraits of the 19th century. In four years, Størmer produced about 500 documentary photographs of life in Oslo, Norway. With his disc-shaped camera tucked beneath his shirt, he would approach strangers on the street, offer a greeting, and snap a photo by discreetly pressing the shutter release against his chest. Most subjects smiled or offered a tip of their hat. Some were confused or irritated. All offered a realistic picture of turn-of-the-century Norway: the styles, the customs, and the city of Størmer’s time.

We don’t know whether or not Størmer got a photo of his sweetheart. We do know that after earning his degree, he pursued a career in mathematics and astrophysics, spending his days penning numerous mathematical publications and working with his own theorem on consecutive smooth numbers2. Later in life, his love for mathematics and photography would collide when he set out to calculate the height and behavior of the aurora borealis. Størmer captured photographs of aurorae from observatories across Norway, and these supported his understanding of the aurora borealis’ behavior within Earth’s magnetic field. To this day, he is considered an authority on the subject.

In his seventies, nearly fifty years since he last buttoned a spy camera beneath his coat, Størmer began to exhibit his collection of secret photographs in Oslo. Today, a great number of these can be found on Norway’s Digitalt Museum.

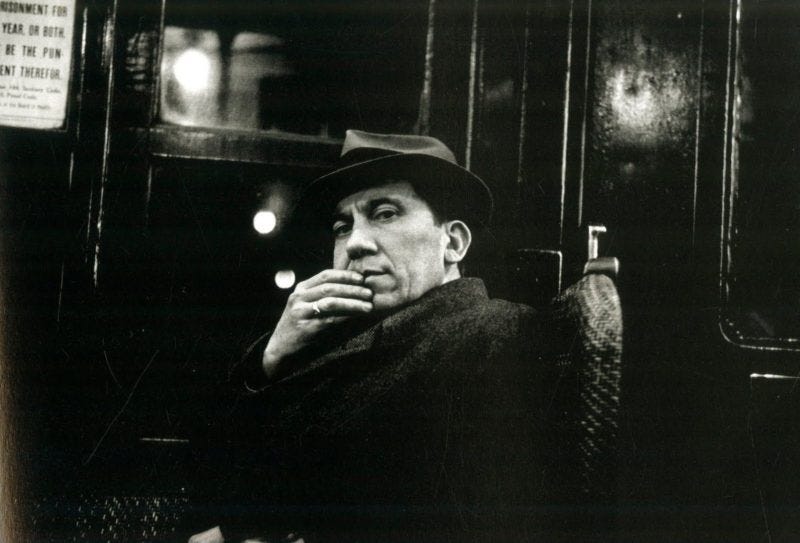

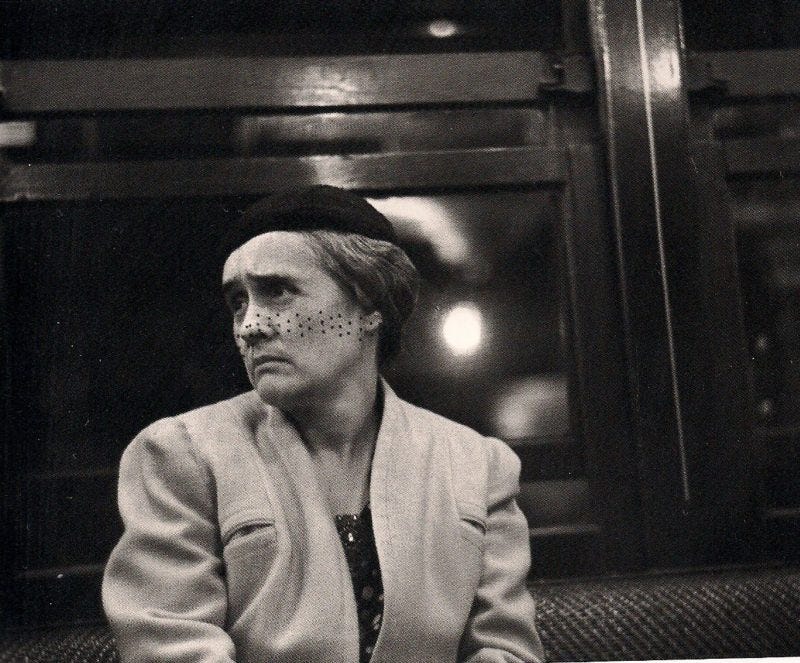

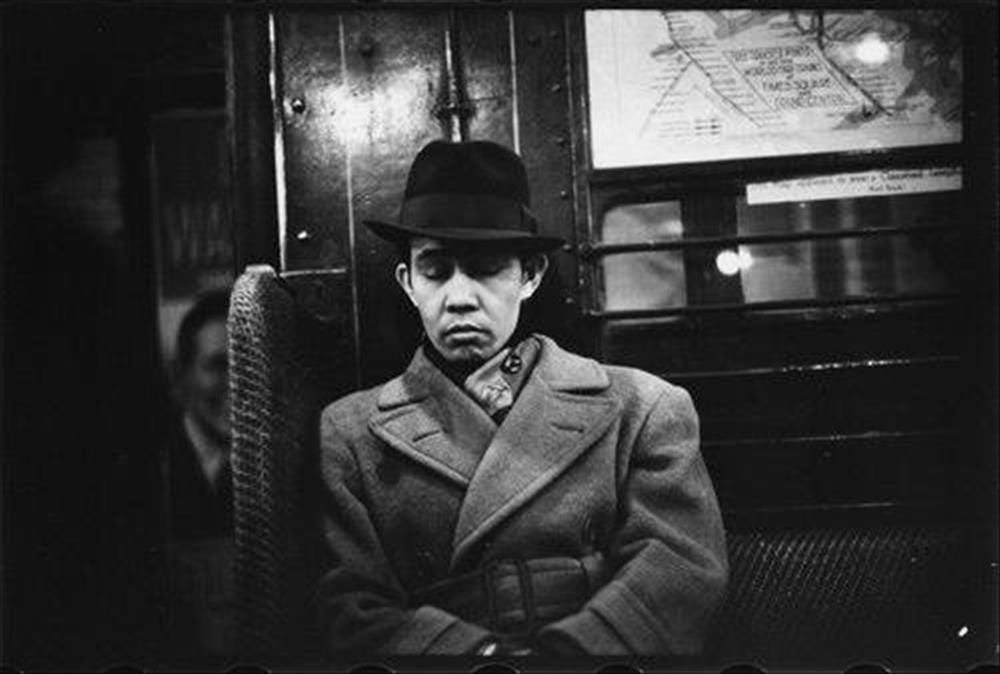

“Underground in the subway, people tend to have their masks off and their guards down more than when one is inside their bedrooms alone. With nothing more to do than wait, you are left alone with your thoughts. We often dive into our thoughts, uncaring about them reflecting on our faces or in our eyes. When we are in a room full of strangers, nobody knows us, our challenges, misery, or joy.”

Walker Evans

By 1938, Walker Evans had been working as a photojournalist for almost a decade. He was known for his “lyrical documentary” style, capturing the mundanity of the everyday in striking, thought-provoking ways. He had spent most of the 1930s employed by FDR’s Farm Security Administration, documenting the Great Depression’s impact on rural America. However, back home in New York and inspired by the realism of Daumier's Third-Class Carriage, he endeavored to capture something even more raw and honest. He decided to secretly photograph his fellow passengers on the New York City subway, pursuing the “idea of what a portrait ought to be: anonymous and documentary and a straightforward picture of mankind.”

Evans painted the lens of his Contax 35mm with black paint, to conceal it more effectively beneath his clothes, and allowed it to poke through the buttons in his coat. In order to facilitate his clandestine approach, he abandoned any effort to manage the camera’s focus, exposure, or flash. He merely ran a shutter release cord down his shirt sleeve, boarded the subway, and waited.

Evans surreptitiously photographed strangers on the subway until 1941. In total, he captured about 600 images.

Twenty-five years later in 1966, after the risk of invading strangers’ privacy had been mitigated by the passage of time, Evans published 89 of his 600 photographs in a book titled Many Are Called, with novelist James Agee providing an introductory essay. That same year, the photos would be exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

When Evans died in 1975, most of his work was bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Though not currently on display, this is where Evans’ hidden-camera subway portraits remain today.

We will never be able to truly see the past. Paintings, illustrations, and sculptures all take shape within the confines of the artists’ style and perspective. Written stories and oral histories will always be a flawed, recollected versions of the past. But Carl Størmer and Walker Evans relinquished the traditional stylistic choices that make photography a subjective medium. They simply photographed the world as it appeared before them.

John Szarkowski, photographer and former director of photography for the Museum of Modern Art, described this process of abandoning subjectivity when discussing Walker Evans’ subway series:

“He had to forego the freedom to choose his angle of view, the control of precise framing, the selection of light, the free choice or direction of his subjects. All that remained was the freedom to say yes or no- to squeeze the cable release hidden in his sleeve or not.”

It is with this passive, unpolished method that Størmer and Evans captured the beautiful, imperfect, and enduring qualities of humanity. Each portrait modestly presents its subjects just as they were a century ago, unburdened by the pressure of performing before a lens.

As always, thanks for reading extracurriculars! For more historical deep dives, oddities, and obscura, consider subscribing below.

For more on Carl Størmer and Walker Evans, check out some of these resources:

The Student Who Caught Ibsen with a Hidden Camera, Alexander Fredriksen-Sylte’s Norwegian language article about Størmer, which includes a very cool sliding image feature to compare the Oslo of Størmer’s time to that of 2021.

Series photographed by Professor Carl Størmer, public domain archive of Størmer’s spy-camera photographs via the Norwegian Folk Museum

Walker Evans’ Many Are Called is no longer in print, and used versions range between $60-$600. To view it without the price tag, you can check your local library or check out this video by PhotoBookLovers on YouTube.

Rules of Civility by Amor Towles opens at Walker Evans’ 1966 exhibition for Many Are Called, and the book centers around the fictional subject of one of Evans’ subway pictures. Rules of Civility is fun for lovers of 1930s ephemera, but its female main character definitely suffers from “women written by men” syndrome.

a gift from his wealthy family; it was very uncommon for the average joe (or carl) to conceal a camera beneath his vest

as the antithesis of a mathematician, I will not be elaborating further. thank you for understanding.

This was a wonderful essay! I've recently started a personal collection of candid photos from the early 20th century. It's fascinating how images of people laughing and relaxed conjure your imagination and transport you that moment in time. <3

I hadn't seen any of these before, and I enjoyed the coupling of two disparate photographers.