The Sex Cult Behind Your Grandma's Silverware

free love, eugenics, and religious fervor: the hidden history of oneida flatware

*Warning: This post contains descriptions of cult behavior & themes of sexual/physical abuse, reader discretion is advised*

The year was 1948, and the American silverware giant, Oneida Limited, was thriving.

Oneida silverware already graced every modern bridal registry and smart tablescape in the country — there’s probably still a chest of it somewhere in a closet at your grandma’s house. But 1948 was exceptional; this year marked record profits in the wake of the war, as well as one hundred years since the company’s namesake, the Oneida Community, got its start. Undoubtedly, a celebration was in order.

On a warm Saturday in July, Oneida Limited hosted its centennial jubilee. Hot dogs and ice cream were served, vaudeville-esque talents performed on stage, and when the sun set, Jimmy Dorsey’s orchestra serenaded dancers under the stars.

Contrast this scene of quintessential American mirth with the events of the year prior, when thousands of documents chronicling the Oneida Community’s early days were loaded into a truck, hauled to a local dump and unceremoniously incinerated.

Reader, you must be asking: why? What could this mega corporation possibly have to hide? Well, to truly understand “the Burning”, as it came to be known, we’ll need to head way back to the early 1830’s.

The United States was in the throes of the Second Great Awakening, an early 19th century religious revival. Centuries-old institutions had collapsed following the American Revolution, and people were seeking enthusiastic and romanticized alternatives to a society riddled with social and economic uncertainty. It was the end times; religious fervor, calls for moral reform, and utopian ideologies swept across the nation like wildfire. Preachers were touring the country, Joseph Smith had just discovered the golden plates of Mormonism on his New York property, and future Oneida Community leader John Humphrey Noyes was studying at the Yale Theological Seminary.

Red-haired, deeply self-conscious, and allegedly still a virgin1, John Humphrey spent his later adolescence lusting after various women and then obsessing over his inability to engage with them. At 21, having suffered greatly under the weight of female rejection, self-deprecation, and pent-up sexual energy, he finally found an outlet in the religious zeitgeist of his time.

While at the Yale Seminary, Noyes was hard at work calculating the time frame for the second coming of Christ, an innocuous hobby for a religious man during this time. But he soon made a shocking discovery. As it happened, Christ had already returned. Like, almost two thousand years prior.

Noyes figured that if society as he knew it existed after the revelation, then the true believers had already been saved. As the keeper of this sacred knowledge, he was an elected agent of God, a prophet, even. It was his duty to bring about heaven on Earth, as the final book of the Bible predicted. He took to the streets of New Haven, preaching about Perfectionism, in which one could be free from sin (and thereby above the law) if they just achieved complete holiness on Earth. Yale caught wind of the content of these sermons, and his right to preach was promptly revoked.

But what religion exists without a little persecution? Noyes eventually made his way back to Vermont, where (despite Yale’s efforts) he continued preaching and gained a decent following. There, he connected with a wealthy convert named Harriet Holton — after she paid off some of his debts — and the two married in 1838. However, according to Noyes’ particular brand of Perfectionism, their marriage was explicitly non-exclusive. As Noyes preached:

“When the will of God is down on earth as it is in heaven there will be no marriage. Exclusiveness, jealousy, quarreling have no place at the marriage supper of the Lamb. I call a certain woman my wife. She is yours, she is Christ’s, and in him she is the bride of all saints.”

Harriet agreed to these terms, and thankfully so. After hearing about a former crush’s engagement to another man, Noyes wrote to inform her of his and her spiritual marriage, in which they were bound in heaven forever, engaging in all manner of celestial sex. The crush in question did not respond, and I can’t say I blame her.

As time passed, the evolution of Perfectionism seemed inextricably tied to John Humphrey Noyes’ romantic inclinations. After being overcome with attraction for the wife of one of his converts, a Mrs. Mary Cragin, Noyes put his theories on divine polyamory into practice. The Noyes and the Cragins began sharing a home and consensually2 entered into a what would later be known as the first “complex marriage”.

“Complex marriage” would probably be described as a polycule today, albeit with far more religious manipulation and rigid heterosexuality. According to Noyes’ teachings, becoming sin-free and achieving heaven on Earth required complete equality and unselfishness. This meant sharing all responsibilities equally among the sexes, as well as sharing all of one’s worldly attachments, including one’s spouse and children. The Perfectionist community, led by Noyes, behaved as one large married family, sharing all of the associated economic, social, and sexual benefits of such an arrangement.

Four additional couples joined the complex marriage (3/4 of whom were Noyes’ sisters and their husbands 🙃), and intercourse was abundant, with Noyes asserting that frequent sex led to immortality. But Noyes and his male converts weren’t satisfied.

They took out ad space in local newspapers to recruit widows and single young women with promises of salvation. While seeking out only women hints at the underlying sexual motives in this purported group of equals, it is also prime example of the cult tendency to seek out the vulnerable. Single women and widows had limited options in 19th century society, and the Perfectionist movement assured their economic and social stability. Predictably, many women capitalized on this opportunity, bringing with them numerous children to be raised under the guidance of John Humphrey Noyes.

With so much “free love” going around, it stands to reason that accidental pregnancy would be a concern. After all, this is a time of limited contraception and obstetric care, and pregnancy was a heavy burden for the women of the community to carry. The Oneida Community was very vocal about female equality (whether or not this translated to real-world practice is up for debate) and they disparaged the idea of pregnancy as women’s burden. So, Noyes’ solution was “male continence”, the idea that sex could, and should, occur without male ejaculation.

In his publication on the topic, Noyes compared male continence to boating near a waterfall: a man could venture into the rapids (have penetrative sex) without going over the falls (ejaculating), provided he had the right amount of practice. Not only did this method favor women’s pleasure and protect them from unwanted pregnancies, it also had a pretty high success rate. Relatively few accidental pregnancies occurred.

Regardless, Noyes’ massive group of husbands, wives, and children garnered some attention in rural Vermont, particularly after Mary Cragin gave birth to his twin children. In October of 1847, he was indicted on charges of adulterous fornication. Immediately following his arraignment, the community absconded to an available3 plot of land in what was known as Oneida Depot, New York.

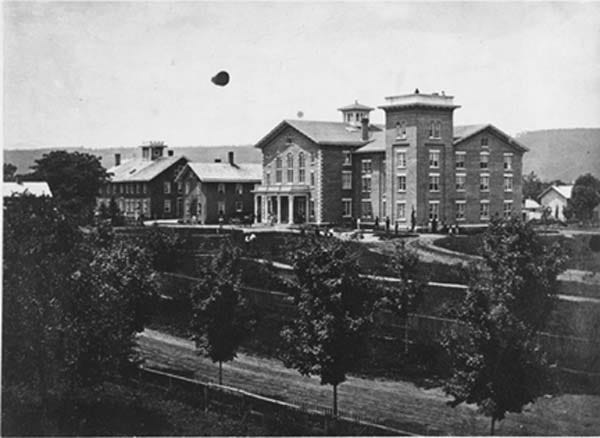

At the time, Oneida was located within “the burned over district”, a hotbed of social reform, religious zeal, and utopian social experiments in Western New York during the Second Great Awakening. In terms of growing a religious cult following, there was no better place for the Perfectionists to settle. Here, they constructed a large wooden house for their 87 members. They established multiple streams of income by crafting various goods. They shared the work in a communistic fashion and manufactured under the name “the Oneida Community”.

In this way, the Oneida Community thrived under Noyes for many years. They lived peacefully on their compound in New York, expanding the home as the community grew into the hundreds. They practiced their religion, published newsletters, ran an efficient home and business, and had lots of sex. They were regarded by their neighbors as peculiar but also kind and hardworking; they held strawberry festivals in the summer and sold their wares in town. Women continued to enjoy freedoms not offered in typical society: they cut their hair short and wore pants to make their work days more comfortable. But lest you begin to consider the Community a progressive experiment in religious polyamory, allow me to remind you of the eugenics detail in this post’s subtitle.

Twenty years after its founding, the original members of the Oneida Community were aging and dying. Noyes, a bit obsessed with immortality, proposed a system of controlled human breeding known as “stirpiculture”; today we would call it eugenics. Before the time of the American eugenics movement, or the more notorious Nazi eugenics movement, Noyes was choosing “perfect” men and women within the Community to concieve “perfect” children with superior mental and spiritual qualities. In this way, his Perfectionist legacy would live on.

As fate (and any cult leader) would have it, Noyes proved to be the most perfect member of the group, fathering 12 of the 58 children bred through the stirpiculture movement. Remember, too, that three of Noyes’ sisters were community members, and at least one child was born to Noyes and his niece, thirty years his junior. By the end, more than half of the 58 children were related to Noyes by blood.

Stirpiculture was intended to pair the most perfect members of the Community, but it was often used as a method of control. As the central arbiter of the movement, Noyes often made pairings with the explicit intention of pairing skeptical members with devout ones, pulling stragglers deeper into the fold.

Though women were allegedly equal to men in the Community, decisions about their childbearing were ultimately made by a man. Women within the Community were expected to show enthusiasm during sexual encounters, but were also shamed for engendering too many “special feelings” in the hearts of the Community’s men. When one woman, Tryphena Hubbard, strayed too far from Noyes’ locus of control, she was put “under the special charge of” her husband, who proceeded to verbally and physically abuse her. One must wonder whether the same circumstances would befall a man in Tryphena’s position.

At the risk of developing “special feelings” for their own children, women were separated from their babies once they reached 15 months of age. The child would thereupon be raised in the “Children’s House” by the community at large. When Charlotte Leonard, a young woman who was brought into the Community as a child, showed too much interest in her 11 month old son, she was separated from him until her feelings could be resolved. During the separation, she wrote:

October 1, 1870 […] It is long since I have recorded any of my experience and I have not cared to do so. God knows what experience I have been through the past year and though it has been the most trying part of my life, I thank God for it all.

October 3 Went to the Children’s House today. Miss Pomeroy is to continue taking care of Humphrey for the present. Cannot tell what may happen, perhaps I shall not have him anymore to take care of at all. But if it be God’s will that I should be so, I know that He will not only make me reconciled but thankful. […]

October 20 Commenced to-day taking care of Humphrey again. The Lord is good to me — very. Father Noyes is so kind and good to me too. [He] proposed to have me take the baby again. This was indeed good news, and I could not keep back the tears. I felt so thankful, and it seemed to me I did not deserve it.

It is difficult to imagine the mental and emotional toll an experience like this could have on a mother, particularly considering the addition of postpartum hormones. But, alas, these decisions were not made by women. They were made by a man who claimed to be their equal.

By the 1870s, tensions within the Community were rising. Some younger members wanted to explore traditional, monogamous relationships. There were arguments over when Community children should be brought into the group’s complex marriage. Boys and girls were initiated (raped) by older members of the Community between 12-14 years old, with Noyes typically initiating girls himself. The very real fact of exploitation was finally being taken seriously by some. Beyond all this, Noyes was well into his sixties, and the question of his successor was a major topic of contention.

Things came to a head in June of 1879, when Noyes was informed that a warrant for his arrest had been issued. He was being charged with statutory rape. In the middle of the night, he fled to Canada, abandoning his Community of nearly 40 years. He never returned. He would die five years later, still living on the Community’s payroll.

From here, the Oneida Community seemed apt to crumble. Theodore Noyes, the only son of Harriet and John Humphrey, attempted to lead but was uncharismatic and, more importantly, agnostic. A large faction of the group broke away, seeking alternative leadership. Complex marriage was abandoned. Difficulties arose in determining who had rights to the Community’s numerous children. Many members experienced traditional society for the first time in their lives.

With the economic and social wellbeing of hundreds of former members hanging in the balance, it was evident that a major change was needed. In 1881, the remaining members abandoned communal ownership of the group’s varied businesses and formed a joint-stock company, Oneida Community Limited.

At the turn of the century, Pierrepont Noyes, one of John Humphrey Noyes’ stirpicult progenies, narrowed the company’s industries to focus on silverware, their most profitable enterprise. The sexual proclivities and fringe beliefs of the company’s predecessors were surreptitiously swept under the rug, allowing the modern and abbreviated “Oneida Limited” to flourish. By the 1910’s, Oneida’s “Community Plate” was a household name. The smartest women were sure to set their table with Oneida’s silver-plated wares.

And so, we circle back to 1947, with firsthand accounts of the Oneida Community’s history reduced to a simmering heap of ash. Polyamory and eugenics were not marketable qualities in post-war America, and John Humphrey Noyes’ descendants were determined to sever ties with their controversial origins for good. And they did; the more salacious details of the Oneida Community remain a relatively well-kept secret to this day.

In 2006, Oneida Limited declared bankruptcy, and in 2021, the company was absorbed by Lenox Corporation. Today, their website glazes over the details that defined so many lives. A blurb reads:

“Oneida was founded in 1848 as an attempt at utopia. Perfection was their goal. To support the community, members made silverware. They became famous, as Oneida's quality was, well, utopian.”

Translated from Greek, “utopia” literally means “no place”. Utopia has and will always be an unattainable myth. Perfection simply does not exist — not at a table with silver-plated service for twelve, not beneath the stars at a corporate celebration, and certainly not within the confines of John Humphrey Noyes’ Oneida Community.

Thanks for reading! For a deeper dive into Oneida’s history, consider picking up Ellen Wayland-Smith’s Oneida: From Free Love Utopia to the Well-Set Table, which greatly informed this post.

For more niche historical musings like this, consider subscribing below.

not a roast just quoting the grievances recorded in his diary

using this term incredibly loosely given the cult association

by “available” I mean “occupied by Natives and illegitimately offered by a white Perfectionist sympathizer”

So interesting, I’ve never heard of this story! It also made me think about how little I know of pre 20th century cults. They seem like such a modern concept but of course the victorians were cultish!

As someone from the Burned Over District, who grew up around the corner from where pre-Mormon Brigham Young lived and whose mother had Oneida cutlery, I remember being shocked when I found out about the Oneida Community- how was no one else talking about this?! lol

This was a great overview on the group- thanks for sharing!