Recently, I had the pleasure of seeing the Boston MFA’s exhibit on Van Gogh’s Roulin family portraits, some of which stand out among the artist’s most well known works.

Van Gogh’s relationship with the Roulin family didn’t just support his work in portraiture; their bond was a port in the storm of his deteriorating mental health. As co-curator Katie Hanson shared with the BBC:

“So much of what I was hoping for with this exhibition is a human story. The exhibition really highlights that Roulin isn't just a model for him – this was someone with whom he developed a very deep bond of friendship.”

I found their story incredibly tender and decided to share it in this week’s post. Enjoy, and if you’re in the northeastern US, stop by the MFA before September!

In February of 1888, Vincent Van Gogh arrived in the South of France hoping for a fresh start. He had spent the previous two years in Paris, where his darker early work evolved into the vibrant, pointillistic style we know today. But, while the artist’s paintings had grown cheerier, the artist himself had not.

Two years in the city had left Van Gogh spiritless and depressed—he was sick from heavy drinking, encumbered by a harsh smoker’s cough, and dejected following yet another failed love affair. He hoped that some coastal air, warm sunlight and bright colors in the seaside town of Arles would bring the artistic fulfillment and emotional tranquility he craved.

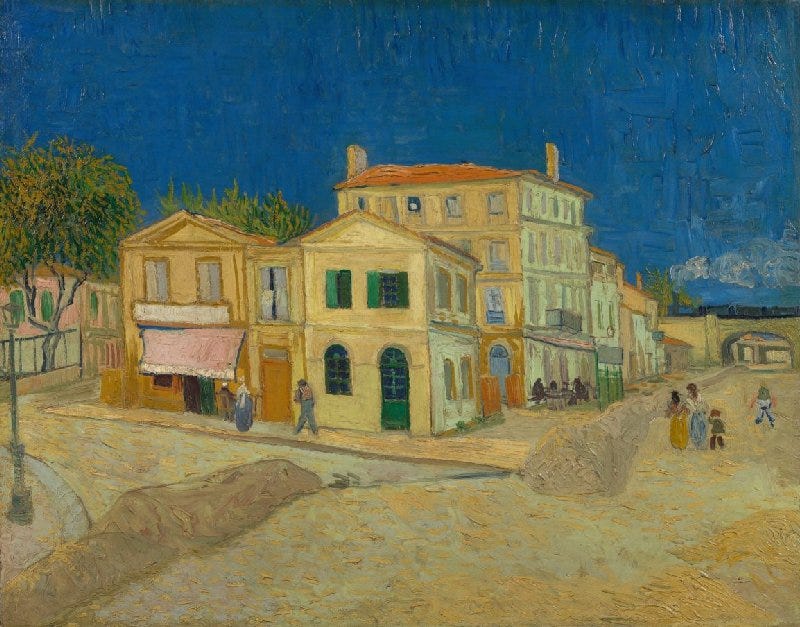

Van Gogh’s dream was to establish an artistic community in Arles where he could work and create among like-minded individuals. As spring warmed into summer, he found the perfect place to start: a narrow, oddly shaped house at 2 Place Lamartine. He wrote to his brother, Theo, about the way the home’s yellow facade and vibrant green shutters contrasted with Arles’ brilliant blue skies.

Settled in the Yellow House, Van Gogh canvassed Arles in search of subjects for his portrait paintings, frequenting the local bars, cafes, and restaurants. He was convinced that portraiture was his calling, and he felt that the people of Arles were more compelling subjects than those he had encountered in Paris. This suspicion was confirmed when he became acquainted with Arles postman Joseph Roulin.

Van Gogh referred to Roulin as “a man more interesting than most”. He was at once stoic and spirited, and his outspoken politics exuded French Revolutionary ideals. He stood at nearly six feet tall, and above his brightly contrasted uniform (which he wore almost constantly), Roulin’s face was “something like that of Socrates, almost no nose, a high forehead, bald pate, small grey eyes, high-coloured full cheeks, a big beard, pepper and salt, [and] big ears.”

It’s not a description that would flatter everyone, but Roulin appreciated Van Gogh’s enthusiasm. The pair hit it off instantly, with one observer noting that they were “like brothers”, each with their fair colored hair and appreciation of a good drink. About a decade Van Gogh’s senior, it’s possible that the painter saw Roulin as the elder brother he never had.1

Joseph Roulin was the postmaster, in charge of sorting the mail at the Arles rail station. He lived down the street from the Yellow House with his wife, Augustine, and their two sons, Armand, 17, and Camille, 11. On the day that Roulin sat for his first portrait, his wife gave birth to a daughter named Marcelle.

By contrast, the 35-year-old Van Gogh led a rather isolated life, with a complicated familial relationship and an exceptional unluckiness in love. In Roulin, he saw his complete opposite, the living expression of everything he once wished to be. Roulin was a man who worked hard, who was devoted to his family, and who maintained an undeterred joie de vivre despite his struggles. With this new friendship, Van Gogh felt closer to his old aspirations than ever before.

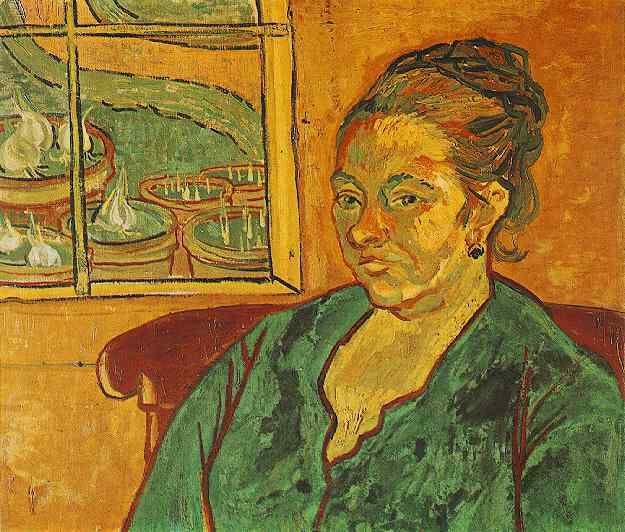

In total, Van Gogh painted 26 portraits of the Roulins, an exceptional number for one family. Their colors are bright and inviting, and their swirling, spontaneous brush strokes seem to indicate a sort of confidence and peace in the artist. He had reignited his artistic passion with portraiture, and with this he felt more in control of his precarious mental health.

Van Gogh’s time in Arles was his most prolific as a painter. He completed over 200 works, filled with bright yellows, deep blues, and cool mauves. He wrote to Theo about his artistic accomplishments, his gratitude for the Roulin family, and his hope master portraiture by his fortieth birthday. Unfortunately, this dream would never be realized. By the end of 1888, Van Gogh’s good fortune had reached its peak.

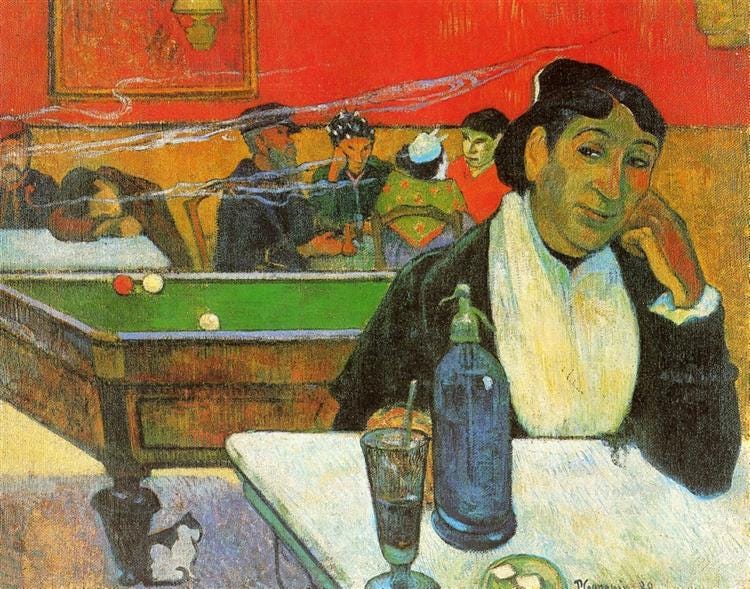

Fellow painter Paul Gauguin joined Van Gogh at the Yellow House in September 1888, after months of repeated invitations. Van Gogh was attempting to cultivate the sort of artistic community he had envisioned in the coastal town, and he imagined that the accomplished Gauguin would be its leader. Gauguin, however, had no intention of remaining in Arles.

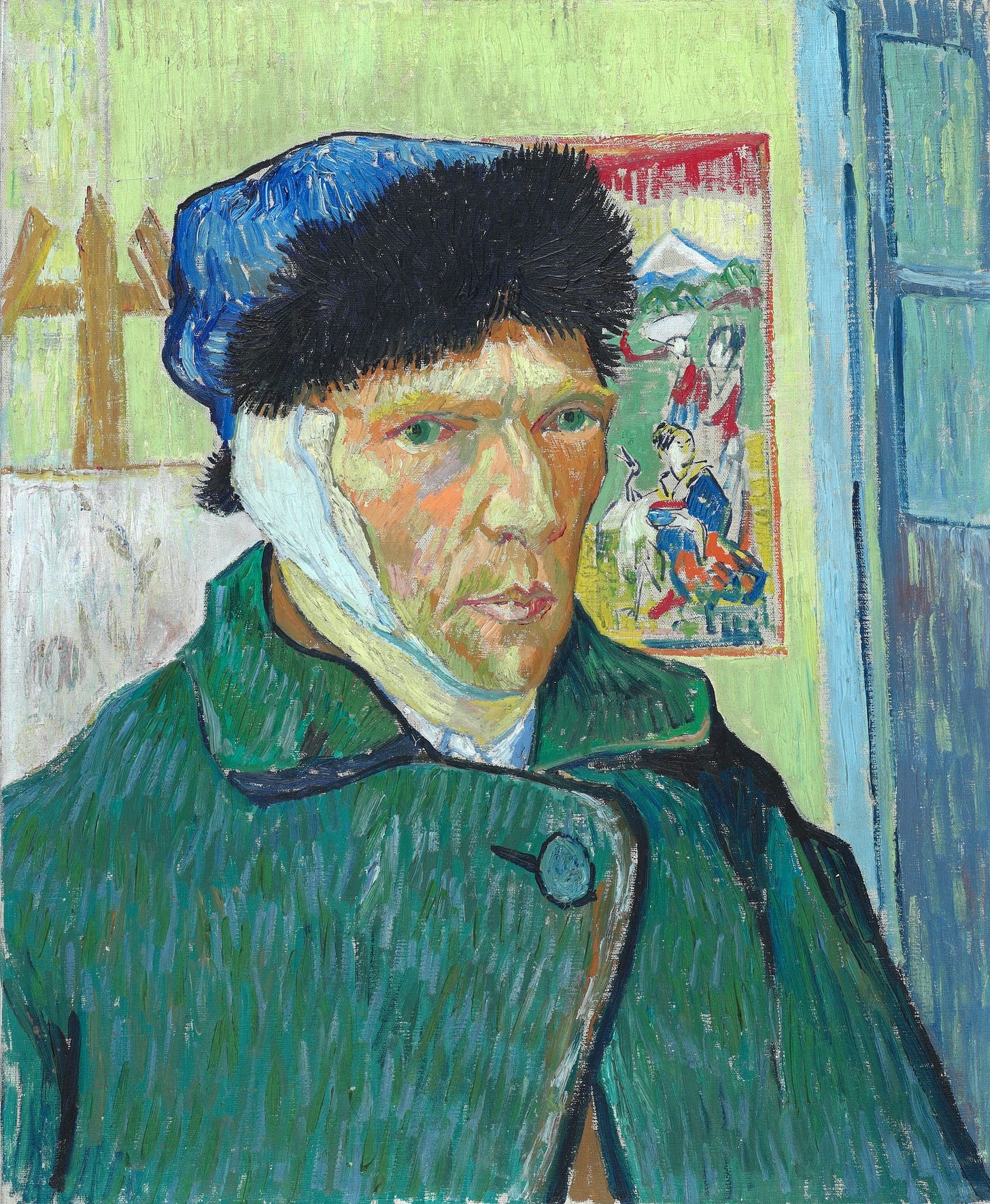

The two artists rarely saw eye-to-eye, and their differences were magnified by their close quarters. Things came to a head one night towards the end of December, when Gauguin revealed his latest portrait of Van Gogh. Upon seeing his likeness, Van Gogh scoffed, “That’s me, alright, but it’s me gone mad.”

The two argued, and Van Gogh became increasingly unstable. When Gauguin threatened to leave Arles altogether, the Dutch painter allegedly chased him through the street with a razor blade. Gauguin checked into a hotel for his own safety while Van Gogh returned to the Yellow House, where he famously sliced off part of his ear.

Theo, newly engaged at the time of the ear incident, was unable to remain in Arles to support his brother’s convalescence. Joseph Roulin, however, was frequently seen at his friend’s bedside.

When Van Gogh was forced to leave Arles following his breakdown, it was Roulin who ensured he receive proper care in a psychiatric hospital and Roulin who maintained the abandoned Yellow House until it was eventually repossessed. Roulin regularly wrote to Theo about his brother’s condition—and many of these letters are on display at the MFA’s exhibit. In April of 1889, Van Gogh wrote that his friend exhibited “a silent gravity and a tenderness […] as an old soldier might have for a young one.”

The time between 1889 and 1890 was incredibly difficult for Van Gogh, and he was plagued by a series of breakdowns. Throughout, he kept close contact with Joseph Roulin. The two continued their correspondence until the 37-year-old artist ended his life in July of 1890.

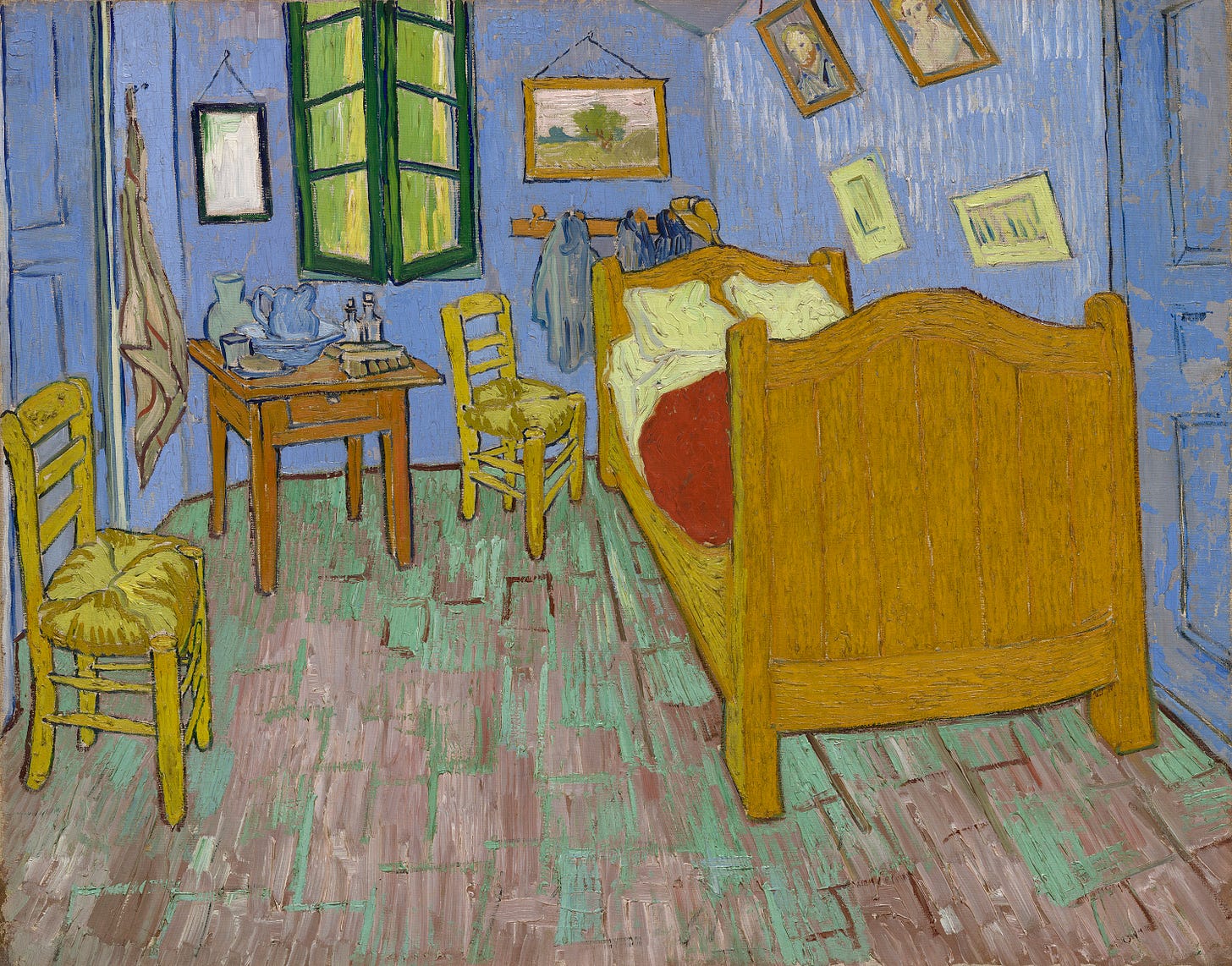

A few months before his death, while confined to a psychiatric hospital, Van Gogh revisited the Yellow House. Likely aware that he would never return to Arles, he chose to repaint his quaint coastal bedroom in serene blues and golden yellows.

In the painting, sunlight creeps through an open window and illuminates the space. The verdant trees signify spring or summer, around the time Van Gogh began painting the Roulins the previous year. Above the bed, two portraits hang. One bears a striking resemblance to Van Gogh, the other depicts a mysterious, fair-haired woman. Is this perhaps a nod to the family he always longed for?

It is difficult to say what would have become of Van Gogh’s stay in the South of France had he not become acquainted with Joseph Roulin, but it is certain that because of this friendship, the painter’s time in Arles was marked by camaraderie and artistic passion, even in light of its chaotic finale. In his portrayal of the blue bedroom, it’s clear that Van Gogh looked back at the Yellow House with a sense of warm nostalgia. He had always wished for a sense of belonging, and in Arles he seemed to finally achieve it, even if only for a moment.

As always, thanks for reading extracurriculars! For more deep dives & niche history like this, consider subscribing below.

For more, check out these resources:

If you can’t make it to the MFA’s exhibit on Van Gogh and the Roulin Family, you can take the audio tour here. If you are in the Boston area, information on the exhibit is available here. If you are near Amsterdam, the exhibit is heading to the Van Gogh Museum in October!

This interview with Marcelle Roulin from 1955 includes a few interesting details about the painter’s friendship with her father. Frankly, my favorite takeaway is the photo of Marcelle with her family’s portraits—adorable.

This reddit post from r/OldPhotosInRealLife compares Van Gogh’s Arles paintings to modern-day Arles. I always love a side-by-side comparison.

A compilation of all of the Roulin family portraits (and their dates of completion) can be found here, courtesy of the Vincent Van Gogh Gallery.

It is worth pointing out that Van Gogh did have an elder brother who unfortunately died at birth