Walls of Death

or, in the words of oscar wilde, “my wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. one of us has got to go.”

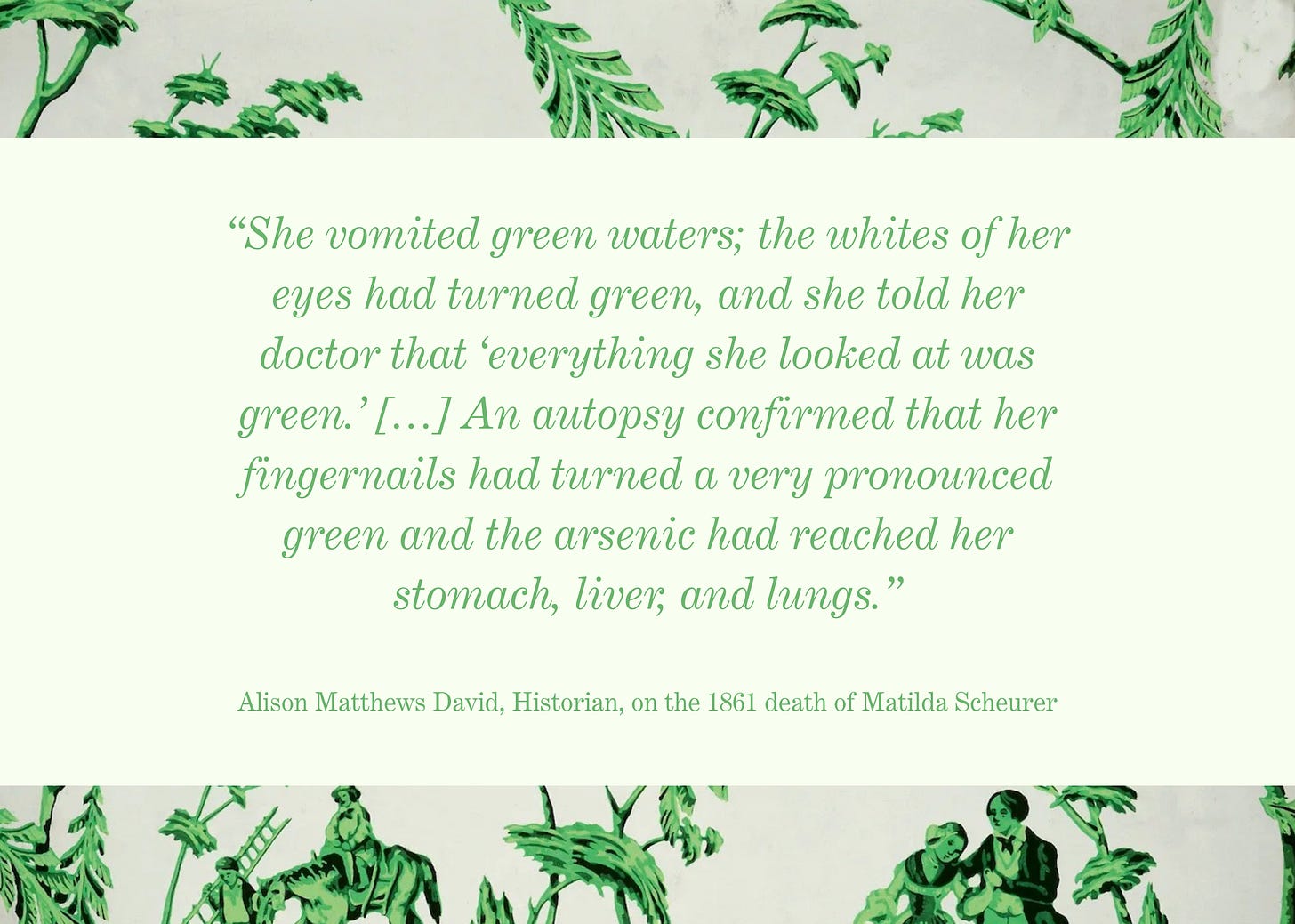

In 1861, nineteen-year-old Matilda Scheurer was supporting her family through factory work. She spent her days crouched over a table alongside 98 other girls, coating artificial flora with bright green powder to achieve a natural look. This powder, made from a combination of copper and arsenic, covered the floors of Matilda’s workplace, stuck to her fingertips as she ate her lunch, and lined her internal organs with every inhalation. Her employer supposedly offered masks, cognizant of the threat a room full of arsenic posed but not concerned enough to halt the use of poison in manufacturing. Matilda and her peers refused, however, due to the excessive heat they experienced in the factory. Masks or not, the danger of chronic arsenic exposure was too great. Matilda’s work would eventually lead to a slow and torturous death.

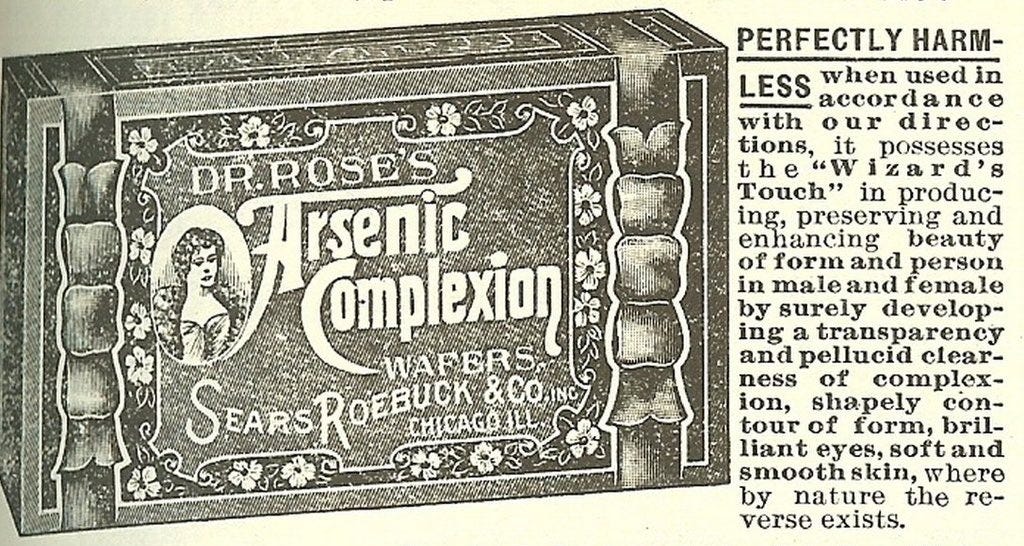

Arsenic’s poisonous potency was well-known in the 1800’s, earning it the tongue-in-cheek nickname “inheritance powder”, but its uses were nevertheless widespread. Yes, it was leading cause of poison-related homicide and suicide. Sure, it directly caused the horrific death of many low-wage workers and unsuspecting consumers. But it was also great for brightening one’s complexion, boosting one’s libido, or treating ailments from syphilis to psoriasis. Perhaps most appealing was its capacity to create a deliciously saturated, inimitable shade of green.

“Scheele’s Green”, as it was known, was wildly popular at the time— think millennial grey for Victorians. It was everywhere: clothing, shoes, upholstery, children’s toys, paints, even food coloring. Because it was generally assumed that arsenic was only poisonous if ingested in large quantities, and because most healthy adults were able to metabolize arsenic in small, intermittent doses, the hazard of coating every marketable item in Scheele’s Green was not readily apparent. As the grey smog of the Industrial Revolution settled over the Western Hemisphere, people longed for the varied, colorful hues of nature. Scheele’s Green allowed consumers to return to the pastoral, verdant ambiance of yesteryear from the comfort of their own home — and this is precisely what people did.

The Victorian attitude for interior design was one of Romantic maximalism, calling for walls adorned with complex patterns, colorfully plumed birds, and decadent florals. In response to popular demand, arsenic was mixed with other popular shades to produce rich, jeweled teals and sunny, canary yellows. Wallpaper production was streamlined, through innovations in block printing and steam-powered presses. In the mere 40 years between 1834 and 1874, wallpaper production in Britain rose by 2,615%. Across the Atlantic, Americans were buying more than 57 million rolls of wallpaper per year. It is estimated that over half of these wallpapers were laced with large quantities of arsenic, slowly releasing poison into the bedrooms, dining rooms, nurseries, and bodies of the unsuspecting masses.

The trouble was that the arsenic was not bound within the wallpaper, it was toxic even when one resisted the temptation to lick the walls. With age and abrasion, arsenic particulate could become airborne, liable to be inhaled by those in the surrounding area. Moisture and heat could also release fatal vapors — and that’s to say nothing of adhesive-borne fungi, which, when combined with arsenic, emitted noxious, garlic-scented fumes. Short of varnishing every wall, a costly and unreliable endeavor, there was really no safe way to bring arsenic wallpaper into a space. This meant that, for almost a century, more than half of all wallpaper owners were chronically poisoned in their own homes.

In the 1850’s, medical literature first began to cite cases of wallpaper induced poisoning. There were stories of unsupervised children who made the fatal mistake of pulling down and ingesting bits of wallpaper. Families whose bedrooms were plastered with arsenic-coated designs found themselves falling mysteriously ill, only to recover after traveling away from home or removing the offensive paper. Even Queen Victoria allegedly had her wallpaper removed after a guest at Buckingham Palace fell ill.

But consumers weren’t the only ones being poisoned. Like Madeline Scheurer, the workers who spent long, underpaid hours in contact with arsenic almost always developed symptoms, many of which would prove deadly. Though the use of arsenic in manufacturing was banned in France, Germany, and Bavaria, other countries were reluctant to abandon the veritable goldmine that was arsenic-pigmented wallpaper, even in the face of its problematic, lethal impact.

William Morris, England’s famed 19th century designer, writer, and activist, made history with his intricately-patterned wallpaper and textile designs. Morris’ wallpaper was incredibly popular during the Victorian era; as a shareholder in the world’s largest copper mine, where arsenic dust was a by-product of mining, sourcing arsenic for his paper’s vibrant colors went without saying.

Morris is remembered not only for his art but also for his strong opinions about social reform. He advocated for worker’s rights and spoke publicly about the rejection of capitalism, co-founding The Socialist League in 1884. Biographer E.P. Thompson argued that Morris’ artistic style was a “passionate protest against [the] intolerable social reality” of industrial capitalism. Yet, when considering his use of poison throughout the mining, manufacturing, and commercial process for his own financial gain, his calls for reform start to seem perfunctory.

In a letter to a friend, Morris dismissed the “deadly wallpaper” allegations, writing: “As to the arsenic scare a greater folly it is hardly possible to imagine: the doctors were bitten as people were bitten by the witch fever.” Morris never visited the mines that financially bolstered his artistic success, where numerous workers suffered and died from arsenic-related complications. He stopped using arsenic in his wallpaper in 1875, not because of any moral code, but due to pressure from a more informed consumer base.

After all, only a year prior, surgeon and chemist R.C. Kedzie published Shadows from the Walls of Death, a book imploring the public to acknowledge the poison lurking in their homes. Kedzie was serving on the Michigan Board of Health when he printed his arsenic-exposé in 1874. His book began with a three-column review of the dangers of arsenic, followed by 86 pages of locally-sourced arsenic wallpaper samples. In a brilliant publicity move, only 100 copies were printed, shipped off to 100 libraries with an explicit warning: the book was to be prominently displayed but was not to be handled by children; its pages were extremely toxic.

Most libraries destroyed the book immediately, and only four copies remain today. But Kedzie’s stunt was effective. He was followed by an onslaught of others in what would become an information campaign against arsenic’s widespread uses. Without any intervention from government or wallpaper manufacturers, consumers themselves responded by seeking alternatives to arsenic-pigmented designs. Companies scrambled to advertise “arsenic-free” paper, and test-kits were available at local drug stores to prove the verity of these claims. By the turn of the century, when lawmakers finally got around to regulating the use of arsenic in wallpaper, Scheele’s Green and its associated shades had already become obsolete.

The story of Scheele’s Green and deadly wallpaper remains fascinating today in part because of its enduring relevance. Though we are no longer pasting poison onto our children’s walls, we still perpetually fall victim to the “money first, public health second” capitalist mindset. Lead pipes still carry water to millions of people in the United States. E-cigarettes generate billions in revenue annually, addicting a new generation of smokers. The fast fashion industry continues to outsource manufacturing in order to dodge regulations and underpay workers. Microplastics, which we are only beginning to understand the impact of, now contaminate the bodies of every living creature on the planet1.

It’s easy to adopt a bleak outlook in the midst of so much disappointment, but I think it’s important to remember our role in this unforgiving capitalist machine. In Shadows from the Walls of Death, R.C. Kedzie called the public to action. Understanding that legislation alone would not limit the production of arsenic wallpaper, he wrote:

“But any legal enactment on this subject, not sustained by an enlightened public sentiment, will remain a dead letter upon the statute book.”

While we can demand more humane, empathetic oversight from the organizations that regulate capitalism, the real change comes when we, the consumer base, withhold our financial contribution. It might not be prudent to withhold water bill payments in demand of non-toxic pipes, but it is perfectly reasonable to minimize (or even abandon) our engagement with unethical businesses. Like the Victorians who refused to bring arsenic into their homes, we too can engender change with the power of our pocketbooks.

After all, as with poison-tinted wallpapers, crazier things have happened.

As always, thanks for reading extracurriculars! For more historical oddities and obscura, consider subscribing below.

For more on the deadly history of arsenic pigments, check out these great resources:

Bitten by Witch Fever by Lucinda Hawksley, both a deep dive into the history of arsenic wallpaper and a gorgeous feast for the eyes

Fashion Victims: The Dangers of Dress Past and Present by Alison Matthews David, which examines the deadly fashion trends of the past, including arsenic-pigmented clothing

Scheele’s Green, the Color of Fake Foliage and Death by Katie Kelleher for The Paris Review

Shadows from the Walls of Death (1874) by Hunter Dukes for The Public Domain Review

And of course, the original Shadows from the Walls of Death by R.C. Kedzie, publicly available via the National Library of Medicine

save for the hardy tardigrades, whose microplastics are merely attached to their limbs

I’ve never learned about William Morris having arsenic in his wallpaper designs! His speaking on workers rights but not reflecting it within his own business is a real reflection of issues we still face today.

I knew I was in for a good time when I saw Victorian wallpaper and a Wilde quote.