Pretty Vacant

On Cynthia, the mannequin who became a real girl, and the strange love affair between humans and their imitations

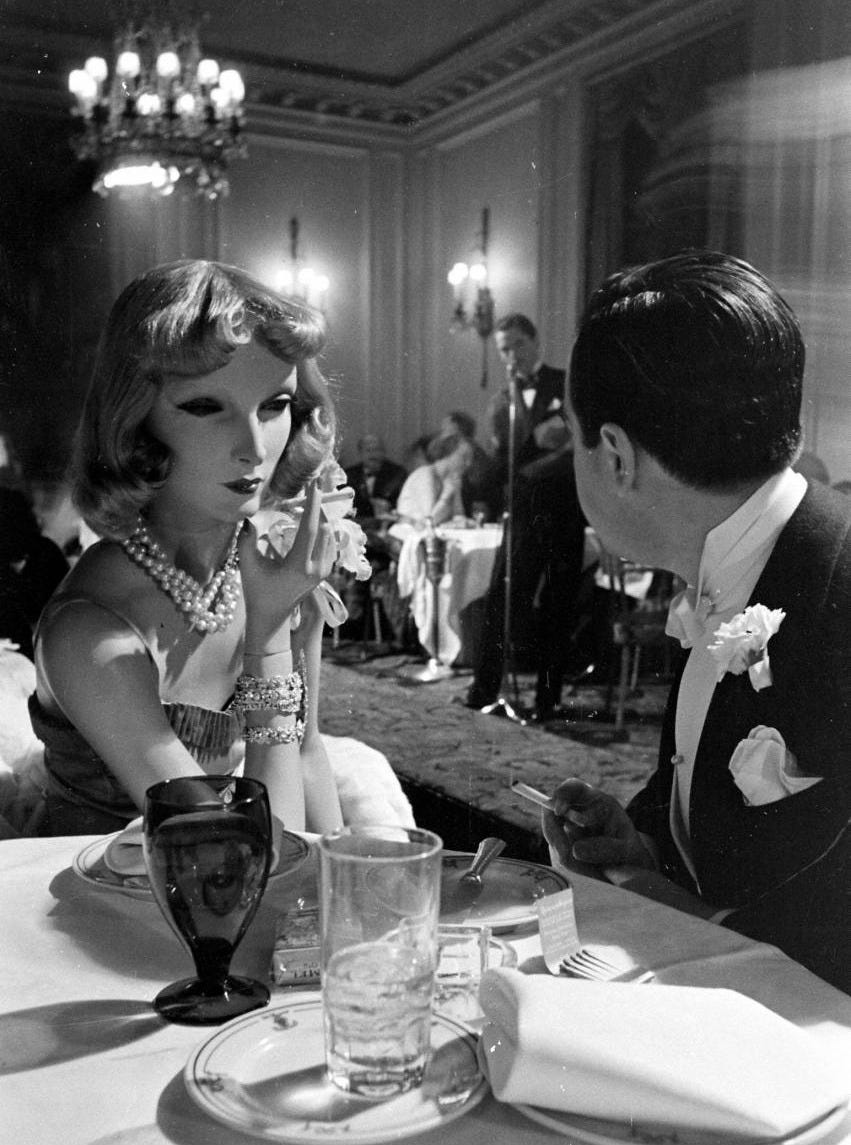

She sat with her back to him, gazing at the commotion beyond—waiters in black suits dashing from table to table beneath a warm electric glow. Smoke rose from her cigarette, casting a haze over her neat curls.

Etiquette suggested that he greet her companion first, so he took Mr. Lester Gaba’s hand firmly in his own and exchanged a few pleasantries. Then, he approached the striking blonde—Cynthia—whose ermine hung carelessly over one bony shoulder.

As he bent for a polite introduction, Cynthia’s manicured hand suddenly detached and bounced clumsily across the restaurant floor. A woman at the adjacent table shrieked: “You brute!”

A waiter stooped to retrieve the hand, raising it with the kind of genial embarrassment reserved for broken wine glasses. Unfettered, Mr. Gaba reached for the disembodied appendage, stood, and screwed it back into place at the end of Cynthia’s outstretched arm. With a series of nods and half-suppressed laughs, the restaurant resumed its dinner-hour chaos.

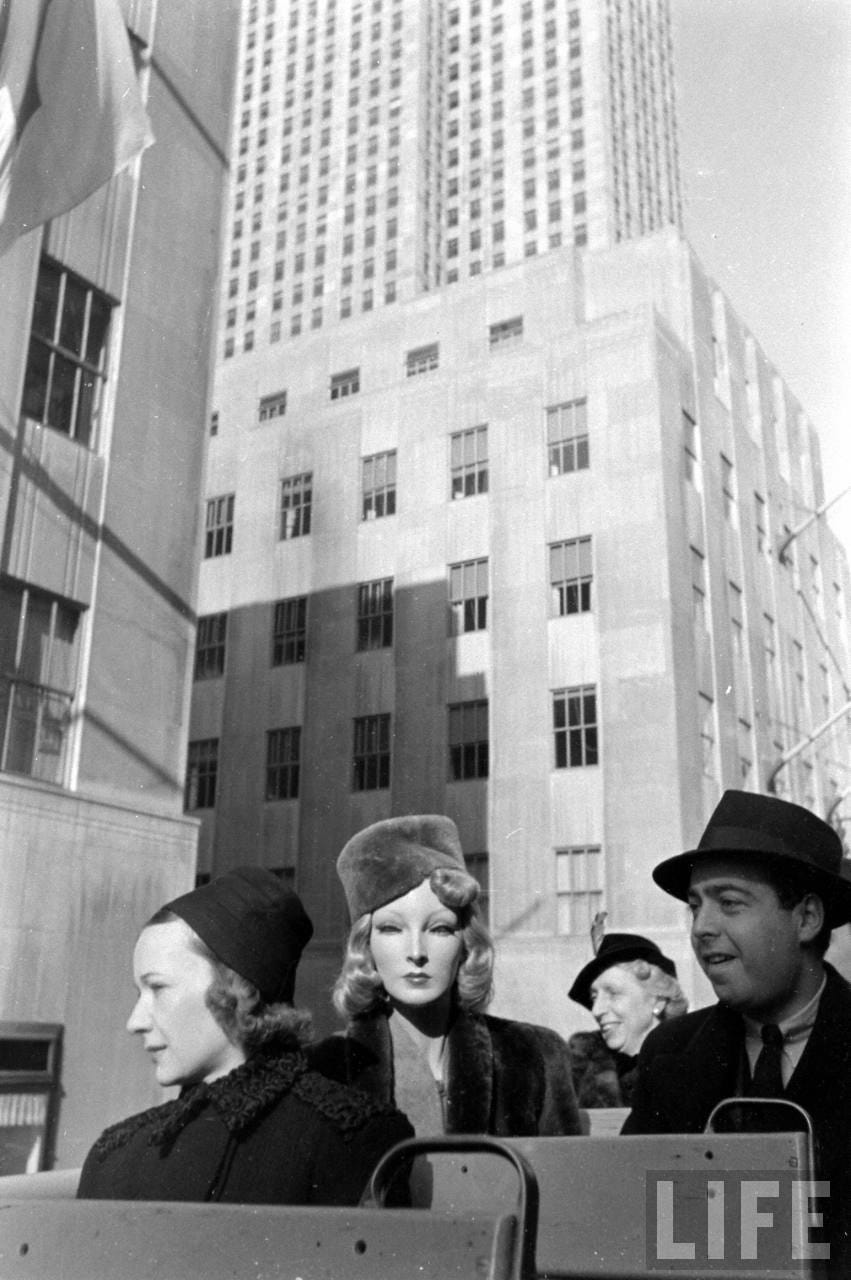

The year was 1937 and, in characteristic New York fashion, the Manhattan crowd had grown accustomed to the uncanny spectacle that was Cynthia, Lester Gaba’s perpetual plus-one. For a year she had blurred the line between reality and fantasy, drawing audiences wherever she appeared. The restaurant episode was merely the latest in a series of evenings where the city pretended, with admirable conviction, that Cynthia was alive.

Constructed in Lester Gaba’s studio five years earlier, Cynthia was the most incredible mannequin the world had ever seen. Her predecessors—amalgams of iron, wood, and wax—were cumbersome, difficult to clean, and had a nasty habit of melting on hot summer days. Their glass-eyed, false-toothed attempts at realism were often more suited to a horror movie than an eye-catching window display.

Lester Gaba—artist and storied champion of numerous Depression-era soap sculpture contests—drastically shifted the mannequin market when he assembled Cynthia from a series of lightweight plaster parts, allowing her to be transported and posed with unprecedented ease. In window displays, Cynthia and her plaster-cast “Gaba girl” companions captivated the public, assuming the poses of living women: elegantly reclined with a cigarette in hand, one leg gracefully balanced atop the other.

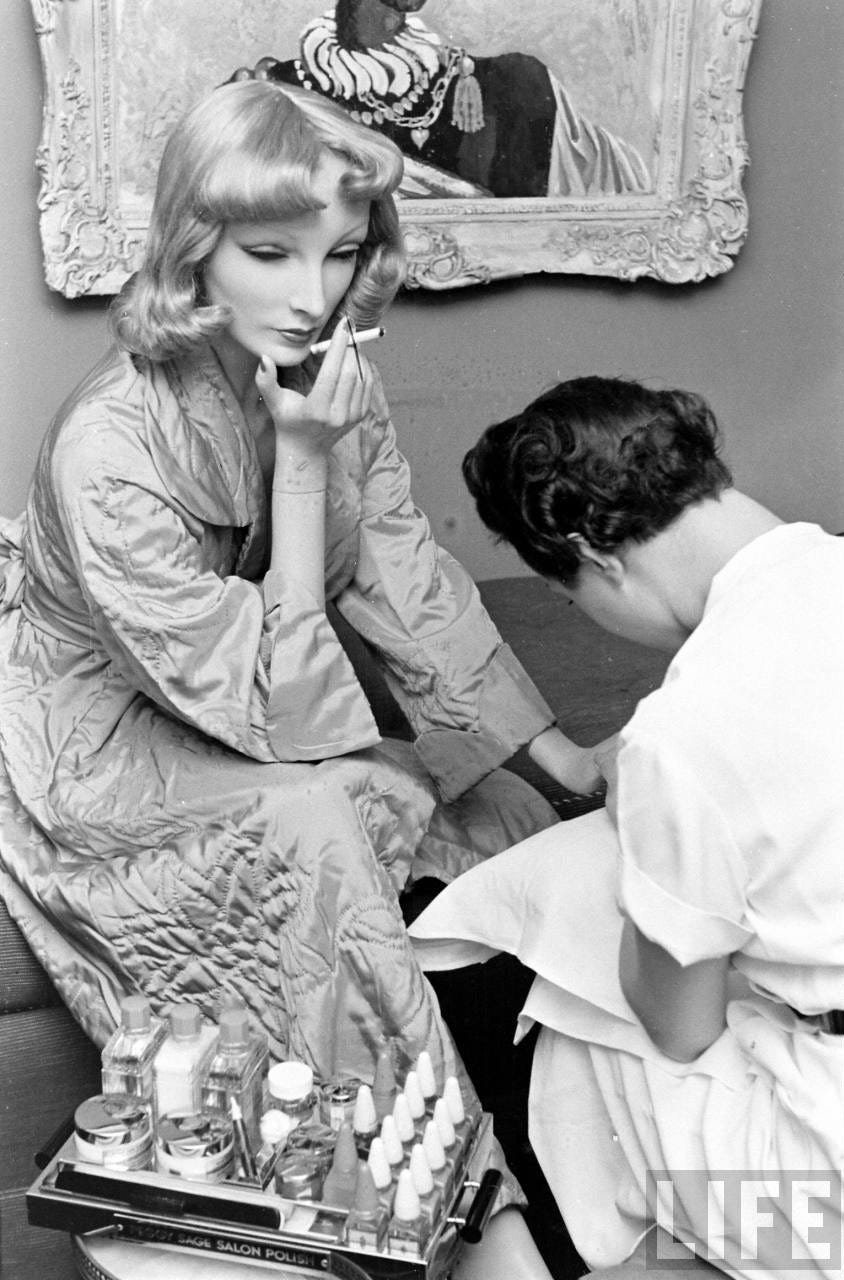

Gaba’s creations toed a fine line between uncanny realism and unattainable idealism, the sort of natural glamour previously reserved for the silver screen. Cynthia possessed details so uniquely human—a sprinkle of freckles across her nose, one foot slightly larger than the other—alongside characteristics straight out of a Vogue magazine spread. Her impossibly thick lashes cast shadows over dramatically painted eyes, her face framed by a halo of blonde curls that would cost the average woman a fortune—and several hours in a salon chair.

Intent on cementing himself as mannequinery’s leading authority, Lester Gaba staged a series of mannequin-based publicity stunts in 1936, pulling Cynthia out from behind the shop-window for a glittering round of evenings on the town. With the air of a newlywed carrying his bride over the threshold, Gaba toted Cynthia to all of New York City’s most exclusive venues, treating her as his real human companion.

Stoic, mute, and dripping in jewels, Cynthia quickly captured the public’s attention—her blend of opulence and absurdity a welcome distraction from the horrors of the mid-1930s news cycle. Gaba quipped that his partner was suffering from a bad case of laryngitis, barring her from conversation with the stars and socialites in their orbit. This quiet elegance soon earned Cynthia a reputation as one of the most glamorous women in Manhattan, despite not being a woman at all.

Mail addressed to Cynthia flooded Lester Gaba’s postbox. She was showered with fan letters, invitations to high-society dinners and galas, and gifts from the most luxurious names in fashion—Tiffany’s, Cartier, and Lilly Daché, to name a few. She was featured in newspaper columns and on radio shows. She was presented with box seats at the Metropolitan Opera. Rumor has it that she was even invited to the Prince of Wales’ wedding, though she unfortunately was not able to attend.

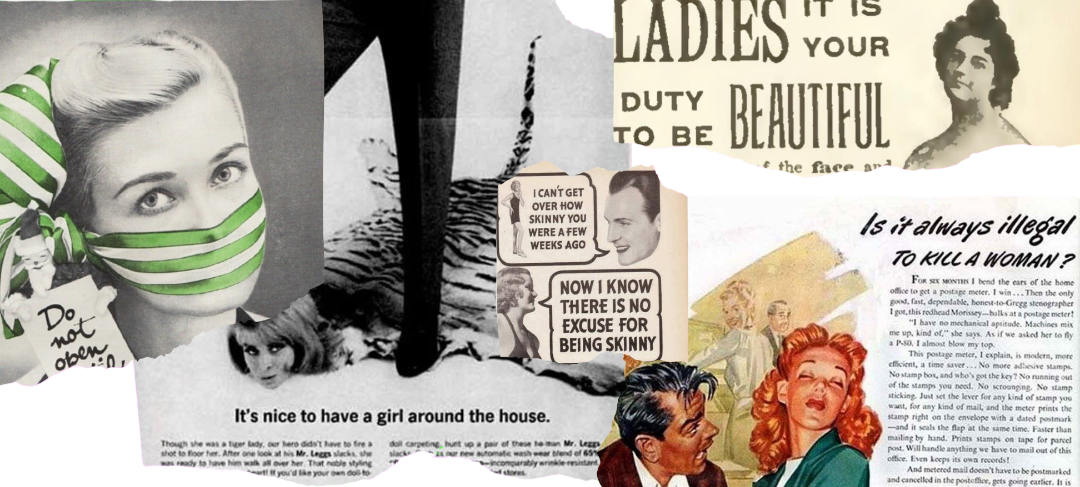

Cynthia led a pseudo-lifestyle that most Depression-era women could only dream of—but perhaps this is what made her so captivating in the first place. While most women were relegated to the domestic sphere, crafting dresses from used feed sacks to save a bit of cash, Cynthia was being featured in major motion pictures, her closet filled to the brim with designer gowns—some with the tags still attached.

It’s possible that Cynthia’s good fortune had something to do with the fact that she possessed all the most alluring aspects of a human woman without any of the associated complications. In an era where a woman’s success was almost always dependent on a man’s approval, Cynthia was designed to be perpetually beautiful, pliable, and silent; more than a few men in 1937 might have argued that she represented the feminine ideal.

In December of 1937, between stories about housing crises and armed revolts, LIFE Magazine ran a story about Cynthia—the “dummy” with the lavish lifestyle. The article painted a tongue-in-cheek picture of Cynthia’s personality, all while maintaining that she was a living, breathing New York socialite.

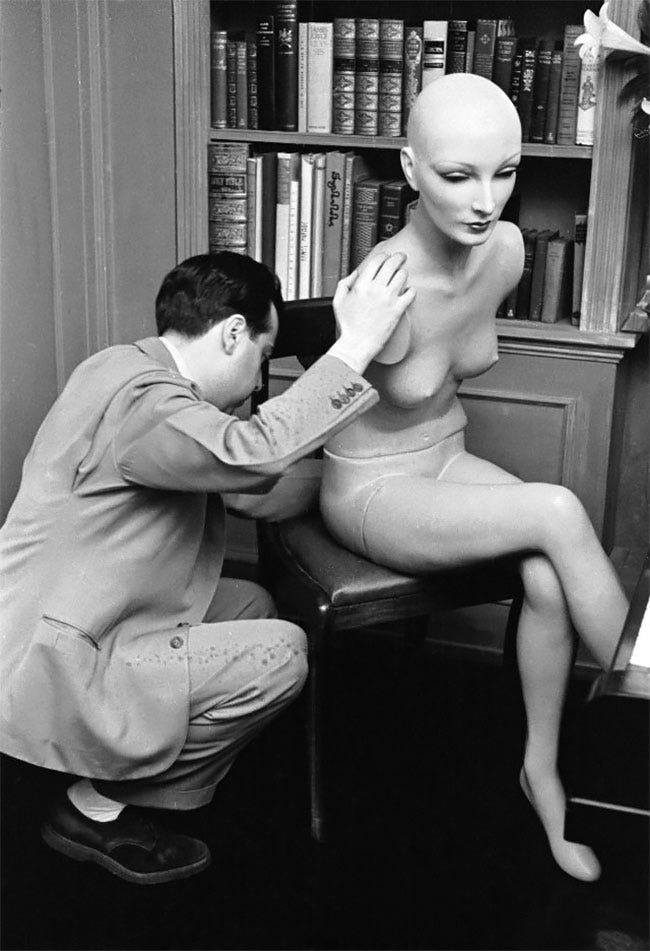

The photo essay recounts a typical day for Cynthia: shopping at Saks, dallying over dinner, and arriving late to the opera. Right away, the author makes note of her indebtedness to Mr. Gaba, as she has him to thank for “everything she has in life”. Below a photo of Cynthia in Gaba’s arms, a caption states that “she never protests any of her benefactors familiarities”. A blank slate in the shape of a human woman, the public could make Cynthia whatever they wanted, and so they made her charming, compliant, and beholden to the generosity of a man.

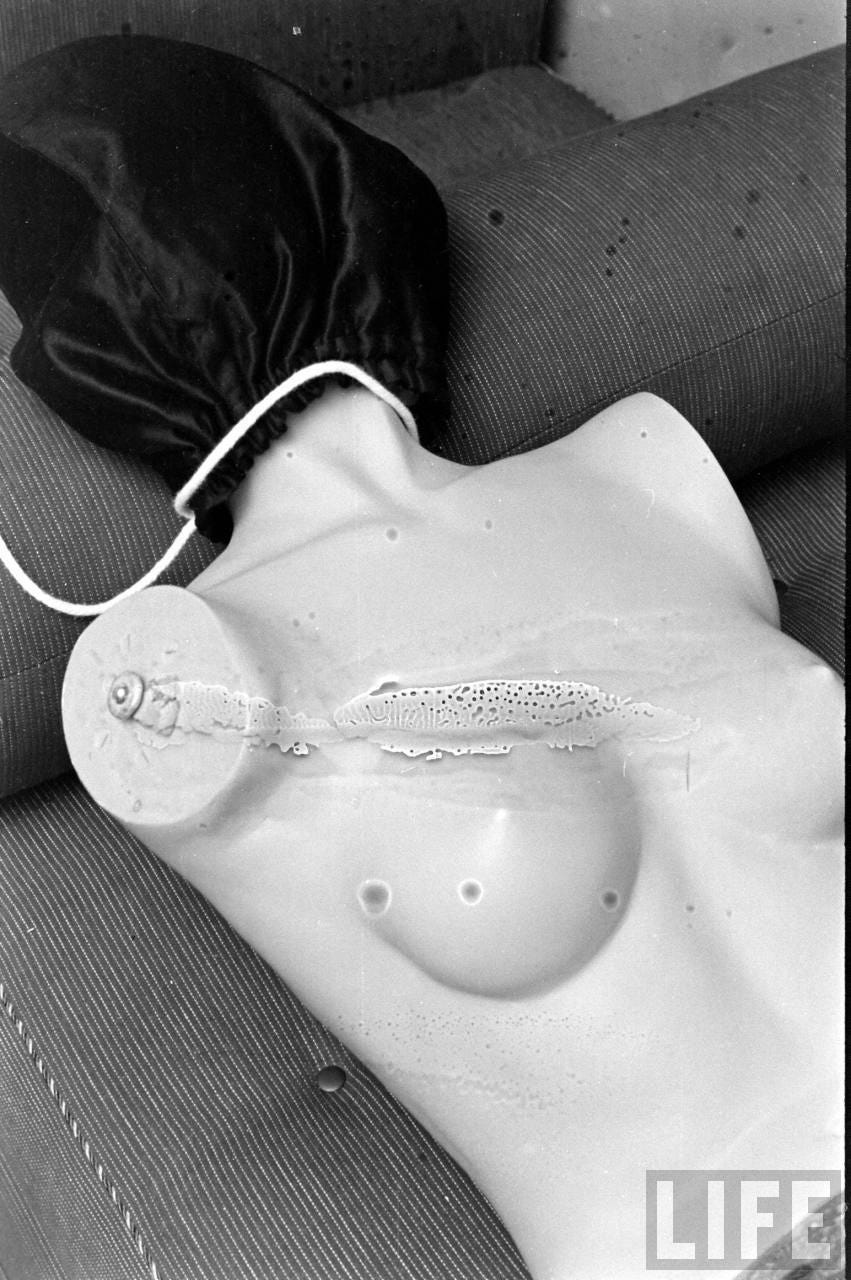

The final images in the photo essay capture Cynthia’s evening routine, during which she is stripped, dismantled, and sealed in a series of black sateen bags. Bold captions reading “Just a dummy” and “Without clothes” accompany photos of Cynthia’s bare torso, her disembodied legs with silk stockings and designer heels still in place.

The impression—apart from reading as some sort of serial-killer-esque fever dream—is that Cynthia is the kind of woman who can be wholly possessed. In LIFE Magazine, a respected and mainstream publication, the public is invited to gaze upon her figure without any societal repercussions. If not, why sculpt her breasts with a pair of true-to-life nipples?

In any case, beauty is fleeting, and Cynthia’s time as New York’s favorite plaster-cast socialite was just as effervescent. It is rumored that, sometime in the late 30s, she suffered a fall from a salon chair and shattered into a thousand pieces, never to be reassembled again. However, it’s more likely that her disappearance had something to do with Lester Gaba’s enlistment in World War II.

While Gaba fought overseas, the mannequins in New York’s storefront windows began to shapeshift. By the time he and the rest of America’s troops returned home in 1945, mannequin hip and bust measurements had doubled, reflecting the curvier ideal of the post-war years. Cynthia and the Gaba girls, in all their slim, sleek Art-Deco glory, faded out of fashion and vanished without a trace.

Though Gaba kept busy as a store window display expert through the 1960s, he never did step out with Cynthia again. He passed away in 1987, and while it’s possible that Cynthia’s black sateen bags are collecting dust in some obscure West Village storage locker, she has not been sighted publicly since.

For a brief while, though, Cynthia provided us a surreptitious glimpse into the psyche of 1930s society—its hidden expectations and desires for women in a complex era of feminism. And while this window into our collective consciousness may have closed, another (massive) door has opened with the rise of AI chatbots and humanoid robots. Our bizarre love affair with Cynthia is far from over; this obsession and all its underlying insights will live on so long as humanity continues to admire, idealize, and abuse its artificial imitations.

As always, thanks for reading extracurriculars! For more deep dives into obscure and niche history, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

For more, check out these resources:

LIFE Magazine’s photo essay featuring Cynthia is available via Google Books, in all its strange and comical glory.

Cynthia’s feature film debut, Artists and Models Abroad (1938), is available on the Internet Archive. She makes a brief cameo around the 44 minute mark.

This post’s title was inspired by a Sex Pistols song. Here’s the link, and never mind the bollocks.

Additional sources for this post can be found here.

If you enjoyed this post, you might also like

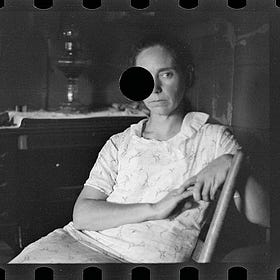

Hole-Punched History

Browse the Farm Security Administration’s photographic archive long enough and you’ll notice a strange pattern. In its massive collection of photographs from Depression-era America, hundreds bear the same glaring, uniform blemish: a circular black void with…

Death & All His Fabrics

From the bell tower atop St. Paul’s Cathedral, a series of muffled bells rang out through the wintry streets of London. It was nearly midnight on December 14, 1861. Earlier that day, newspapers had reported that the King consort, Prince Albert, was gravely ill and deteriorating. The solemn tones emanating from St. Paul’s that night confirmed the worst: …

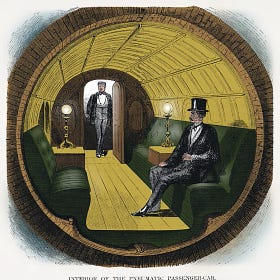

The Beach Pneumatic Transit

For today’s post, you’ll be heading back to New York City in the year 1870. For your sake, we’ll choose a nice, clear morning in May— though “clear” is a bit relative. You’ll notice an ever-present industrial smog hanging along the rooflines.

Fascinating! this reminded me of three movies: Simone, Lars and the Real Girl and of course Mannequin!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HuAjeuKXX7c

Humans are so weird indeed

i love cynthia so much, she will endlessly fascinate me <3 i mean, she’s my profile pic on here and my phone wallpaper haha! i even wrote an ode to her for a class assignment once. your larger analysis is very thoughtful - i think mannequins in general always tell us a lot about the gender politics of when they were made and are so overlooked in art history + cultural analysis. great piece :) !!